An overview of the Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group (SwissNeoNet)

Introduction

Contrary to common belief, Switzerland has a considerable degree of heterogeneity affecting clinical research. There are ca. 8 million inhabitants of which a third have a migration background. They live in four culturally diverse regions, each with its own language: the German, French, Italian, and Romansh part of Switzerland. Health care is organized federally by the 26 cantons which sometimes makes national coordination of research and quality control difficult. Of the ca. 80,000 newborns per year, 7.5% are preterm and 1% are very preterm. Between 1980 and today, the rate of very preterm birth doubled from 0.5% to 1% (1).

The Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group (SwissNeoNet) started off as an isolated paper form collection of a minimal neonatal dataset (MNDS) of all very preterm, live-born infants below 32 weeks’ gestation and/or below 1,501 g birth weight in Switzerland from 1995 to 1996. Hans Ulrich Bucher, the former director of the Department of Neonatology at the University Hospital Zurich and long-term president of the Swiss Society of Neonatology, initiated the collection for outcomes research and modeled the dataset according to the one developed by the Vermont Oxford Network (VON) for very low birthweight (VLBW) infants below 1,500 g (2). This dataset encompassed the essential perinatal and neonatal processes and outcomes that were known to be common for very preterm born infants, e.g., provision of antenatal steroids as an example for processes and late onset sepsis as an example for outcomes. The quality and reliability for research of the VON dataset had recently been tested (3). The SwissNeoNet dataset was augmented by several parameters to support local research interests which led to two initial publications on infant transfers and cystic periventricular leukomalacia (4,5).

Bucher laid great emphasis on observing the long-term development of very preterm born infants on a population based level. It has been previously demonstrated that short term outcome measures, derived at the end of the primary hospitalization period, had limited predictive validity on the future health status of the preterm child (6). Also, most long-term outcome data available were of limited generalizability as they usually represented a possibly biased selection of former preterm children without proven representation of the target population. In 1998, Prof. Bucher thus initiated a first Swiss population based outcome assessment at 2 years using a parental questionnaire sent to all parents of surviving infants from the year 1996; 68% of the families responded revealing quantifiable growth retardation and developmental delay (7).

As of the year 2000, SwissNeoNet had established a nationwide continuous MNDS of all very preterm born infants between 22 0/7 to 31 6/7 weeks’ gestation or below 1,501 g birthweight. For all surviving extremely preterm infants born between 22 0/7 to 27 6/7 weeks gestation, this MNDS was combined with two follow-up assessments at 2- and 5.5-year of age. As of 2006, these assessments were standardized throughout Switzerland: the 2-year assessment consisted of a general physical assessment, a developmental test according to the Bayley Scales for Infant Development, 2nd edition, a sensory-motor-neurological examination for cerebral palsy and other issues, as well as a test each for visual and auditory problems. As of 2011, the 3rd edition of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development replaced the former one. The 5.5-year assessment consisted of the same tests as for 2 years except that the Bayley test battery was replaced by Kaufmann-ABC and Kaufmann-ABC II as of 2011, respectively (8).

In 2011, the data collection was augmented by the “Asphyxia” dataset for neonates requiring therapeutic hypothermia due to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. This data collection is coupled with the same 2- and 5.5-year follow-up assessment as used for extremely preterm born children.

In 2019, SwissNeoNet expanded the MNDS data collection by two additional gestational weeks, i.e., from 32 0/7 to 33 6/7, termed B34, to provide data for research on moderately preterm infants and to allow a quality collaboration between all level III neonatal intensive care units’ (NICUs) with all level IIB peripheral intermediate care neonatal units (NUs), which will be described in greater detail below.

In this review, we will summarize the structure and organization of SwissNeoNet, its current activities and collaborations, engagement activities for participating members, current and future challenges and what our future plans are.

Structure and organization

SwissNeoNet currently coordinates research and quality collaboration for all Swiss NICUs and NUs (Table 1). Also participating are the 16 neuro-/developmental pediatric units performing the 2- and 5.5-year follow-up assessments, a list of which was previously published (8). The network operates under the auspices of the Swiss Society of Neonatology and is governed by a Steering Committee (3 to 5 elected representatives) and a Scientific Committee encompassing the unit directors of the 9 NICUs. The costs for SwissNeoNet’s administration and infrastructure are covered by a fee paid by all participating NICUs and NUs whereas the NICUs pay additionally for quality assessment and collaboration. The network receives no support from government. Its budget corresponds to ca. 1.75 full time equivalents.

Table 1

| Hospital | City | Level | Director |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s Hospital | Aarau | III | Philipp Meyer, MD |

| University Children’s Hospital | Basel | III | Sven Schulzke, MD, MSc |

| University Hospital | Berne | III | André Kidszun, MD |

| Children’s Hospital | Chur | III | Thomas Riedel, MD |

| University Hospital | Geneva | III | Riccardo Pfister, MD |

| University Hospital | Lausanne | III | Jean-François Tolsa, MD |

| Children’s Hospital | Lucerne | III | Martin Stocker, MD |

| Children’s Hospital | St. Gallen | III | Bjarte Rogdo, MD |

| University Hospital | Zurich | III | Dirk Bassler, MD, MSc |

| Cantonal Hospital | Baden | IIB | Elvire Ettel, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Bellinzona | IIB | Monica Ragazzi, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Biel/Bienne | IIB | Matthias Gebauer, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Buelach | IIB | Urs Zimmermann, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Fribourg | IIB | Benedikt Huber, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Muensterlingen | IIB | Bernd Erkert, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Neuchatel | IIB | Ikbel El Faleh, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Sion | IIB | Juan Llor, MD |

| Children’s Hospital | Winterthur | IIB | Lukas Hegi, MD |

| Cantonal Hospital | Zollikerberg | IIB | Vera Bernet, MD |

| University Children’s Hospital | Zurich | IIB | Cornelia Hagmann, MD |

| Triemli City Hospital | Zurich | IIB | Maren Tomaske, MD |

The chief aim of SwissNeoNet is to maintain and/or improve the quality and safety of medical care for high-risk newborn infants and their families in Switzerland through a coordinated program of research, education and collaborative audit.

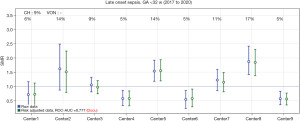

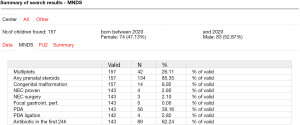

In support of its aim, SwissNeoNet hosts the official medical quality register for Swiss NICUs and NUs, whose participation in the program is mandatory. For this, the network developed an online web-application starting in 2007 in which all units deposit and have continuous access to their local data. They also have access to standardized mortality and morbidity ratio (SMR) charts that compare their clinic with all other clinics individually (Figure 1), compare their longitudinal development with the remaining clinics using p-charts (Figure 2) and perform customized numerical evaluations that compare their unit to all other units combined (Figure 3). The SMR is a ratio between the observed events of a quality indicator at a clinic over expected events after indirect standardization towards the reference. The entire collective as reference is set as 1 and the unit’s value per indicator is displayed in relation to the collective value with a 95% confidence interval. The p-charts display the effect size of an indicator over time with one dot per year for the given unit versus the rest-collective. Horizontal lines reflect the mean rate over time, one for the unit and one for the rest-collective, respectively, as well as one each for the unit’s first, second and third standard deviation of the mean value. Within the diagrams, the user can toggle between different sub-collectives (e.g., <32 or <28 weeks’ gestation). The SMR charts can additionally be displayed for different time periods between 2006–2020 with time periods pooling up to 4 years for better statistical inference. A list of variables is shown in Table 2. Data collection and evaluation for research studies are approved by the Swiss Association of Research Ethics Committees (BASEC; PB_2016-02299). Participating centers are obliged to acquire an informed consent with the patient’s legal representative and inform them about the scientific use of anonymized data.

Table 2

| Nr | Quality indicator | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inborn | Process |

| 2 | Any prenatal steroids | Process |

| 3 | Full prenatal steroids | Process |

| 4 | Caesarean section | Process |

| 5 | Mortality | Outcome |

| 6 | In hospital mortality | Outcome |

| 7 | Survival without severe morbidity | Outcome |

| 8 | Early onset sepsis | Outcome |

| 9 | Late onset sepsis | Outcome |

| 10 | Culture negative late onset sepsis | Outcome |

| 11 | Death or late onset sepsis | Outcome |

| 12 | NEC | Outcome |

| 13 | Surgery for NEC | Outcome |

| 14 | Death or NEC | Outcome |

| 15 | Spontaneous intestinal perforation | Outcome |

| 16 | Intracraneal haemorrhages, grade 3–4 (sIVH) | Outcome |

| 17 | Death or sIVH | Outcome |

| 18 | Cystic PVL (cPVL) | Outcome |

| 19 | Death or cPVL | Outcome |

| 20 | PDA treated | Outcome |

| 21 | Surgery for PDA | Outcome |

| 22 | Death or PDA | Outcome |

| 23 | Retinopathy stages 3–4 (sROP) | Outcome |

| 24 | Death or sROP | Outcome |

| 25 | Oxygen at 36 weeks GA (BPD) | Outcome |

| 26 | Death or BPD | Outcome |

| 27 | Partial milk feeding at discharge home | Process |

| 28 | Moderate/severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years | Outcome |

| 29 | Death or mod./sev. NDI at 2 years | Outcome |

NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; cPVL, cystic periventricular leukomalacia; sIVH, Intraventricular Haemorrhage Grade 3 or higher; sROP, Retinopathy of Prematurity Stage 3 or higher; GA, gestational age; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; NDI, Neurodevelopmental Impairment.

SwissNeoNet places a considerable amount of its resources into the constant upkeep and further development of its web application to foster data completeness, center collaboration, research and quality control, as well as safeguarding a secure repository. The web application fulfills the information technology security standards confidentiality, accountability, data integrity and availability. Confidentiality is achieved by restricted access (qualified password protection, center- and person-specific user rights, encrypted transactions using Transport Layer Security), accountability by access logs, data integrity by recording when a dataset was first setup and each time that it was changed (date, user, field changed, content changed) and availability by performing continuous backups, updating and renewing the infrastructure cyclically, as well as by possessing a disaster recovery and business continuity process plan. The SwissNeoNet data collection is monitored for population coverage, dataset completeness, plausibility and reliability. MNDS data quality is additionally audited by comparing a randomly selected 10% of all datasets with their original patient history in each unit in a 3-year rotation. Five NICUs transfer data from their electronic health records to SwissNeoNet, the remaining use the case report forms of our online web application. A list of items, their definitions and more information on the data collected by SwissNeoNet can be found on the website of the Swiss Society of Neonatology (SSN) (https://www.neonet.ch).

Within this context, SwissNeoNet was invited to assist the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences in setting up quality criteria required for all Swiss national medical registries. Once the academy finalized its testing criteria, SwissNeoNet and its web application passed the audit as one of the first Swiss medical registries (9).

In comparison to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office birth registry, SwissNeoNet covers ca. 96% of all live births in the MNDS. We assume that the 4% missing cases are predominantly from the lower end of gestational age as peripheral clinics without intensive care capacity report delivery room deaths to the government but not to us. For survivors below 28 weeks’ gestation, a stable follow-up rate around 85% of all survivors at 2 years was established once SwissNeoNet offered its users online recruitment tools within its web application (8). At 5.5 years, intense efforts over several years were required to reach a stable value between 70–75% of surviving extremely preterm infants per year, mainly because it was difficult to keep track of young families that tend to move more often than established families. One helpful approach was to send reminders to the families between the 2- and 5.5-year follow-up in the form of Christmas cards. Another was to raise the awareness among general pediatricians on the need for a follow-up assessment performed by neuro-/developmental pediatricians also for healthy former extremely preterm infants, by occasionally publishing reports in Swiss medical journals (8,10,11). The participation in MNDS in combination with the 2- and 5.5-year follow-up is mandatory for the Swiss perinatal centers based on government regulations on quality assessment. The participation in the B34 collection has recently been made a requirement for annual accreditation of NICUs and NUs, which is why we expect to have full coverage but were not yet able to compare with the Federal Statistical Office as no data as of 2019 was available to date. The participation in the asphyxia registry is voluntary. However, since all but one smaller unit performing therapeutic hypothermia actively participated between 2011 and 2018, we believe our data collection to be almost population based [Adams et al. (12)]. In 2019, the remaining unit joined.

Activities as network

Participating units may use the collected data for research after presenting a detailed abstract of the planned research to all units involved. Units may actively participate in the proposed study. If they do not want their data to be used, they need to opt out actively. SwissNeoNet co-authors all resulting manuscripts as a consortia and disseminates all research in peer-reviewed medical journals.

Several of these studies provide direct feed-back to the participants at SwissNeoNet, for instance by providing orientation on how the performance of Swiss neonatology compares to other nations. For instance, a comparison of VLBW infant outcomes between the Swiss and the US NICUs of the VON, representing 95% of all Swiss and 84% of all US live births, revealed a higher mortality for Swiss units but a lower risk ratio for death or major morbidity, independent of survival bias (13). In a comparison with 7 other national networks collaborating in the International Network for Evaluating Outcomes of Very Preterm Neonates (iNeo), Swiss NICUs had the lowest standardized ratio for death or major morbidity, again in VLBW infants, but the highest odds for adverse outcome in very preterm infants with severe congenital heart defect (14,15). Some studies inform how different approaches in practices without clear evidence base compare to each other and which better benefit the newborn, for instance concerning lower or higher perinatal interventional activity for extremely preterm born infants, or whether fewer or more infants require surgical PDA ligation (16,17). Another study of former very preterm born Swiss children aged 12, revealed that they experienced their health-related quality of life as equivalent to their peers, even though neurodevelopmental impairment was still observable (18). We believe these studies support SwissNeoNet’s aim for improving quality and safety of medical care in Swiss neonatology.

The data collected is also used for direct quality assessment and comparison between NICUs. To coordinate these efforts, SwissNeoNet created a quality improvement collaborative in 2011 and since releases an annual quality report to each NICU (19). This report currently lists 29 quality indicators that are compared between the NICUs and with an international benchmark (Table 2). The indicators were selected by a panel of experts and encompass the main processes and outcomes for very preterm infants. They were tested for their suitability as quality indicators using the strict criteria of QUALIFY (20). QUALIFY was developed by the German National Institute for Quality Measurement in Health Care (BQS) as an instrument for the structural appraisal of quality indicators in health care. It offers 3 criteria for the proposed quality indicator’s relevance, 8 for its scientific soundness, and 9 for its feasibility. To discuss quality issues and for educational purposes, SwissNeoNet hosts bi-annual meetings/symposia for the NICU directors group and the follow-up group, respectively. During the first annual meeting of the NICU directors group, all quality indicators of the previous year are commonly viewed and discussed, whereas all NICUs are openly identifiable. The directors then select two indicators for the second meeting based on their clinical need for attention. During the second meeting, the two directors of the NICUs with the potentially worst and best performances regarding these two indicators each collaborate in finding differences in their local approaches and present them to the remaining directors. This approach informs the entire group of possible local improvement potential and has actually led to several local quality improvement projects whose long-term effectiveness is monitored by SwissNeoNet and is currently being evaluated for publication.

A similar procedure is planned for the collaboration of NICUs and NUs by comparing neonatal processes and outcomes for infants born between 29 0/7 and 33 6/7 weeks’ gestation using the MNDS and B34 data collection. As some of the NUs are small, several years need to be pooled to allow statistical inference.

Apart from process and outcome data, SwissNeoNet also collects structural data for the Swiss Committee for the Accreditation of Neonatology Units. This committee annually supervises all NICUs and NUs on whether they maintain predefined requirements on infrastructure, staffing and admitted patients (21).

SwissNeoNet supports the neonatal units logistically to ensure that each patient receives primary care (NICU bed availability tool) and neurodevelopmental follow-up assessments at 2 and 5.5 years (follow-up missing lists) to support long-term surveillance of neurodevelopmental outcomes, and early diagnosis and intervention where needed. Its online app offers tools for unit-to-unit quality improvement collaboration (see below). With regards to its follow-up program, the SwissNeoNet also supports training of new staff and coordinates the launch of new testing batteries between centers.

Current within country and outside of country collaboration

SwissNeoNet entered its first international collaboration in 2005 with the EuroNeoNet (ENN) which was initiated and directed by Adolf Valls-i-Soler of Bilbao, Spain (22). SwissNeoNet’s aim in collaborating was to benchmark within geographical proximity and to help build a neonatal research community within Europe. After Prof. Valls-i-Soler’s sudden and sad demise, Dominique Haumont from Brussels took over the initiative for a combined European neonatal network named eNewborn at which SwissNeoNet was one of the founding members (23). Thanks to eNewborn, Swiss NICUs were able to perform online benchmarking with NICUs from Belgium, Czech Republic, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, who submitted data extracted from an in-country database. Additionally, data submitted by individual neonatal units from 5 additional countries were available for comparison: France 10 units, Germany 1 unit, Poland 1 unit, Spain 2 units, and Finland 1 unit. The eNewborn data repository has recently moved to London with Neena Modi as new director. SwissNeoNet is honored to be part of this future network which will be using the data also for research collaboration alongside the benchmarking facility.

In 2011, the Swiss NICUs were invited to participate in VON, the largest neonatal network encompassing more than 1,000 NICUs worldwide. On behalf of the Swiss NICUs, SwissNeoNet set up an interface in which the Swiss data is transformed to fit the VON coding specifications. Thanks to this partnership, Swiss NICUs receive an annual quality report in which VON compares a large selection of processes and outcomes among the participating NICUs as reported by Horbar et al. (24).

In 2013, SwissNeoNet joined iNeo, a collaboration of population-based national neonatal networks including Australia and New Zealand, Canada, Finland, Israel, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Tuscany, and the UK. The aim of iNeo is to provide a platform for comparative evaluation of outcomes of very preterm and VLBW neonates to generate evidence for improvement of outcomes in these infants (25). Thanks to the tireless efforts and commitment of its director, Prakeshkumar Shah of Toronto, Canada, this collaboration has been the most productive one resulting in more than 20 publications in peer-reviewed journals. Some of the publications focus on comparisons of neonatal outcomes between networks, others link results from a unit-level survey to patient-level cohort data to inform on treatment and outcome variation of patent ductus arteriosus, necrotizing enterocolitis or retinopathy of prematurity (26-28). To the Swiss neonatologists, they provide highly useful orientation on how neonatal processes are differently performed in other parts of the world and which approach is associated with higher or lower adverse outcome.

Within Switzerland, SwissNeoNet is known best for its quality improvement concept and its expertise of collecting primary hospitalization data in combination with follow-up data and is thus frequently consulted by other medical registries. It has close ties to SwissPedNet, the Swiss Research Network of Clinical Pediatric Hubs and hosts the Swiss neurodevelopmental outcome registry of children with severe congenital heart disease (ORCHID).

Together with the Academy of Fetomaternal Medicine of the Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics, SwissNeoNet hosted two national perinatal days to foster an exchange between obstetricians and neonatologists and discuss mutual clinical issues. As a result, the official Swiss guidelines for the application of antenatal steroids were revised, and those for the application of magnesium-sulfate for neuroprotection were set up (29). A future collaboration with a national obstetrical registry is planned.

Engagement activities for participating members

The coordinator of SwissNeoNet, Mark Adams, regularly presents the network and its availability to perform research to certified neonatologists in training at the Swiss Neo4Neo summits. This has led to several investigator initiated research studies with SwissNeoNet data and biostatistical support (30-33).

The afore mentioned web application assists participating members to collaborate between different neonatal units. It hosts a list of all running and completed studies, an overview over running events at which members can participate or which they can initiate themselves, a forum to discuss issues openly or restricted to selected users, as well as a survey builder so that surveys can be submitted to members within a secured environment and responses are saved on a local server. This survey builder is most often used to perform unit-level surveys on treatment issues, e.g., for predominantly empirically treated problems such as necrotizing enterocolitis or patent ductus arteriosus. Depending on specific access rights granted by the unit director, participating members can evaluate historical data to research the feasibility of prospective studies or whether sufficient data is available to research possible associations between processes and outcomes (see also Figures 1-3).

Challenges—current and future

SwissNeoNet has a lot of potential to be exploited for years to come. Over the past 2 decades, a growing number of publications revealed that collaboration within a neonatal network is associated with improved care and therefore improved outcome. These results are particularly striking in those areas, where decades of research and several attempts at testing new interventions with randomized controlled trials have failed, such as in the prevention and treatment of infections. The participation in the national surveillance and/or quality improvement collaborations of VON (34), the Evidence Based Practice for Improving Quality program of the Canandian Neonatal Network (35), or the German NEO-KISS (36) have led to markedly reduced infection rates within years, after decades of continuously high rates. This growing awareness of the effectiveness of collaborative audit exemplifies one of the large potentials of our network which we already are in the process of exploiting. At the same time, this potential is coupled with an ongoing challenge. Because it is so far not possible to directly link the effect of quality improvement collaboration with improved outcome, receiving the required funding to guarantee continuous operation of a multifaceted, complex network with an electronically advanced, security sensitive infrastructure remains challenging.

Over the years, the amount of data that SwissNeoNet routinely collected grew in size. Whereas we started with ca. 90 items for the initial MNDS, we now routinely collect ca. 2,000 data items (37). Therefore, another constant ongoing challenge is to maintain a high quality among the collected data while constantly expanding the dataset. We meet this challenge by organizing data item definition, validation, import, and export in a single, central repository around which all raw data routines are grouped (38). After data entry, users receive immediate feed-back on data quality and completeness and need to work through error lists until data is complete. Currently, we are collaborating with Cistec, the company that provides the electronic health record to almost half of the hospitals participating in SwissNeoNet. We are setting up a secure Web service so that the neonatal units can transfer their data directly from their patient’s electronic health record and in return receive a report on missing/erroneous data directly into their report. This will allow a more timely collection of data rather than the current by-annual lump collection of all infants born during the previous semester. It also paves the way to expand the collection of data for research into the era of big data and personalized medicine.

Future directions/plans

For the immediate future, SwissNeoNet is in the process of expanding its quality report to include infants born up to 33 completed gestational weeks in order to provide NUs with data on where local improvement potential may lie.

In 2019, SwissNeoNet was asked by the Swiss Personalized Healthcare Network to design a standard dataset to be collected for every Swiss newborn for future use in personalized medicine. After designing such a dataset largely based on the experience of the MNDS for very preterm born infants, we expect that within a few years it will be possible to expand research and quality assessment beyond SwissNeoNet’s current inclusion criteria (39).

Hospital data on mortality and clinical outcomes alone however do not inform us about the patient’s experience of wellbeing and what happens after discharge home. The data collected by SwissNeoNet for instance may reveal that a patient was discharged home stable and without any major morbidity. It however says little about how the parents experienced their child’s wellbeing after discharge, which outcomes parents consider as being important for their child’s quality of life, whether surgeries were performed that took place after discharge home (e.g., for a ventricular shunt, to treat retinopathy of prematurity or an innate heart condition to name the most frequent forms) or if the child had to be re-hospitalized because of complications. These issues are of clinical relevance and some may be associated to the quality of care the child received at the NICU. For this reason, SwissNeoNet is now looking into the possibility of collecting patient reported outcome measures (PROM) by building a prospective parent data repository, ideally linked to the repository of the newborns. PROMs are standardized, validated questionnaires to assess patient perspectives of care outcomes in contrast to patients’ experience of the care process (40). In adult medicine, they provide a remarkably sophisticated measure of whether a treatment has worked in the rather important sense of whether the patient feels better, and how much better (41).

Currently, SwissNeoNet is testing its technical abilities for a PROM repository in a single-center pilot study. We setup a survey builder in which an individual without Web programming experience built a complex questionnaire for parents to assess childhood respiratory issues in former very preterm born infants. The survey can be accessed by parents by reading a QR-code using their smartphones. This will take them directly to a questionnaire available in as many languages as required which can easily be read and completed by any chosen device, i.e., that is platform independent. In summary, we believe that learning more about the parental/patient perspective would benefit clinical research, qualitative research, quality assessment, long-term follow-up recruitment and may even pave the way to later expand into citizen science and personalized health care.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all children and their parents who participated in SwissNeoNet. We also thank the following members of SwissNeoNet for their non-author contributions: Aarau: Cantonal Hospital Aarau, Children’s Clinic, Department of Neonatology (Ph. Meyer, R. Kusche), Department of Neuropaediatrics (A. Capone Mori, D. Kaeppeli); Baden: Department of Pediatrics, Cantonal Hospital Baden (E. Ettel); Basel: University Children’s Hospital Basel (UKBB), Department of Neonatology (S. M. Schulzke), Department of Neuropaediatrics and Developmental Medicine (M. Brotzmann); Bellinzona: San Giovanni Hospital, Department of Neonatology (M. Ragazzi); Department of Pediatrics (G. P. Ramelli, B. Simonetti Goeggel); Berne: University Hospital Berne, Department of Neonatology (J. McDougall), Department of Pediatrics (T. Humpl), Department of Neuropaediatrics (M. Steinlin, S. Grunt); Biel: Children’s Hospital Wildermeth, Department of Pediatrics (M. Gebauer), Development and Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Center (R. Hassink); Buelach: Departement of Neonatology, Reginal Hospital Buelach (U. Zimmermann); Chur: Children’s Hospital Chur, Department of Neonatology (T. Riedel), Department of Neuropaediatrics (E. Keller, Ch. Killer); Fribourg: Cantonal Hospital Fribourg, Department of Pediatrics (B. Huber); Department of Neuropediatrics (G. Blanchard); Geneva: Department of Child and Adolescent, University Hospital (HUG), Neonatology Units (R. E. Pfister), Division of Development and Growth (P. S. Huppi, C. Borradori-Tolsa); Lausanne: University Hospital (CHUV), Department of Neonatology (J.-F. Tolsa, M. Roth-Kleiner), Department of Child Development (M. Bickle-Graz); Lucerne: Children’s Hospital of Lucerne, Neonatal and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (M. Stocker), Department of Neuropaediatrics (T. Schmitt-Mechelke, F. Bauder); Muensterlingen: Cantonal Hospital Muensterlingen, Department of Pediatrics (B. Erkert, A. Mueller); Neuchatel: Cantonal Hospital Neuchatel, Department of Pediatrics (I. El Faleh, M. Ecoffey); Sion: Department of Pediatrics, Cantonal Hospital Sion (J. Llor); St. Gallen: Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, Department of Neonatology (A. Malzacher), Children’s Hospital St. Gallen, Neonatal and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (B. Rogdo), Department of Child Development (A. Lang-Dullenkopf); Winterthur: Cantonal Hospital Winterthur, Department of Neonatology (L. Hegi), Social Pediatrics Center (M. von Rhein); Zollikerberg: Hospital Zollikerberg, Neonatal Unit (V. Bernet); Zurich: City Hospital Triemli, Neonatal Unit (M. Tomaske), University Hospital Zurich (USZ), Department of Neonatology (D. Bassler, R. Arlettaz), University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Department of Neonatology (C. Hagmann) and Child Development Centre (B. Latal, R. Etter).

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Shoo Lee and Prakesh Shah) for the series “Neonatal Networks for Outcomes Improvement: Evolution, Progress and Future” published in Pediatric Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-21-76/coif). The series “Neonatal Networks for Outcomes Improvement: Evolution, Progress and Future” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. MA receives a salary as coordinator of SwissNeoNet. DB is a member of the Steering Committee of SwissNeoNet. DB is also an unpaid editorial board member of Pediatric Medicine. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Statistik B für. Gesundheit der Neugeborenen. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/gesundheitszustand/gesundheit-neugeborene.html

- The Vermont-Oxford Trials Network. very low birth weight outcomes for 1990. Investigators of the Vermont-Oxford Trials Network Database Project. Pediatrics 1993;91:540-5.

- Horbar JD, Leahy KA. An assessment of data quality in the Vermont-Oxford Trials Network database. Control Clin Trials 1995;16:51-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bucher HU, Fawer CL, von Kaenel J, et al. Intrauterine and postnatal transfer of high risk newborn infants. Swiss Society of Neonatology. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1998;128:1646-53.

- Bauder FH, von Siebenthal K, Bucher HU. Ultrasonically established cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL): incidence and associated factors in Switzerland 1995-1997. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol 2000;204:68-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sostek AM, Smith YF, Katz KS, et al. Developmental outcome of preterm infants with intraventricular hemorrhage at one and two years of age. Child Dev 1987;58:779-86.

- Bucher HU, Killer C, Ochsner Y, et al. Growth, developmental milestones and health problems in the first 2 years in very preterm infants compared with term infants: a population based study. Eur J Pediatr 2002;161:151-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Borradori-Tolsa C, Bickle-Graz M, et al. Follow-up assessment of high-risk newborns in Switzerland. Paediatrica 2014;25:6-10.

- Medizinische Register. Empfehlungen zum Aufbau von Registern für Entscheidungsträger aus Verwaltung, Politik und Öffentlichkeit (Stakeholder) im Gesundheitswesen sowie Registerführende in der Schweiz 2015. Available online: https://www.samw.ch/dam/jcr:af9000ec-0e95-4e08-9336-79b8da652950/bulletin_samw_14_3.pdf

- Adams M, Bucher HU. the Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group. Neonatologie: Ein früher Start ins Leben: Was bringt ein nationales Register? Schweiz Med Forum 2013;13:35-7.

- Pittet-Metrailler MP, Mürner-Lavanchy I, Adams M, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at early school age in a Swiss national cohort of very preterm children. Swiss Med Wkly 2019;149:w20084. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Brotschi B, Birkenmaier A, et al. Process variations between Swiss units treating neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and their effect on short-term outcome. J Perinatol 2021;41:2804-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Bassler D, Bucher HU, et al. Variability of Very Low Birth Weight Infant Outcome and Practice in Swiss and US Neonatal Units. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20173436. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah PS, Lui K, Sjörs G, et al. Neonatal Outcomes of Very Low Birth Weight and Very Preterm Neonates: An International Comparison. J Pediatr 2016;177:144-152.e6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norman M, Håkansson S, Kusuda S, et al. Neonatal Outcomes in Very Preterm Infants With Severe Congenital Heart Defects: An International Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e015369. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Berger TM, Borradori-Tolsa C, et al. Association between perinatal interventional activity and 2-year outcome of Swiss extremely preterm born infants: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024560. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Schulzke SM, Natalucci G, et al. Outcomes for Infants Born in Perinatal Centers Performing Fewer Surgical Ligations for Patent Ductus Arteriosus: A Swiss Population-Based Study. J Pediatr 2021;237:213-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Natalucci G, Bucher HU, Von Rhein M, et al. Population based report on health related quality of life in adolescents born very preterm. Early Hum Dev 2017;104:7-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Hoehre TC, Bucher HU, et al. The Swiss Neonatal Quality Cycle, a monitor for clinical performance and tool for quality improvement. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:152. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reiter A, Fischer B, Kötting J, et al. QUALIFY--a tool for assessing quality indicators. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich 2007;101:683-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

-

Standards for Levels of Neonatal Care in Switzerland 2019 . Available online: https://www.neonet.ch/application/files/7715/6880/5956/Level_Standards_2019-03-14.pdf - Valls-i-Soler A, Carnielli V, Claris O, et al. EuroNeoStat: a European information system on the outcomes of care for very-low-birth-weight infants. Neonatology 2008;93:7-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haumont D. NguyenBa C, Modi N. eNewborn: The Information Technology Revolution and Challenges for Neonatal Networks. Neonatology 2017;111:388-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horbar JD, Soll RF, Edwards WH. The Vermont Oxford Network: a community of practice. Clin Perinatol 2010;37:29-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah PS, Lee SK, Lui K, et al. The International Network for Evaluating Outcomes of very low birth weight, very preterm neonates (iNeo): a protocol for collaborative comparisons of international health services for quality improvement in neonatal care. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isayama T, Kusuda S, Reichman B, et al. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit-Level Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treatment Rates and Outcomes in Infants Born Extremely Preterm. J Pediatr 2020;220:34-39.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Darlow BA, Vento M, Beltempo M, et al. Variations in Oxygen Saturation Targeting, and Retinopathy of Prematurity Screening and Treatment Criteria in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: An International Survey. Neonatology 2018;114:323-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams M, Bassler D, Darlow BA, et al. Preventive strategies and factors associated with surgically treated necrotising enterocolitis in extremely preterm infants: an international unit survey linked with retrospective cohort data analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031086. [Crossref] [PubMed]

-

Expertenbriefe-SGGG 2021 . Available online: https://www.sggg.ch/fachthemen/expertenbriefe/ - Gerull R, Brauer V, Bassler D, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and ROP treatment in Switzerland 2006-2015: a population-based analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018;103:F337-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rüegger C, Hegglin M, Adams M, et al. Population based trends in mortality, morbidity and treatment for very preterm- and very low birth weight infants over 12 years. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen F, Bajwa NM, Rimensberger PC, et al. Thirteen-year mortality and morbidity in preterm infants in Switzerland. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:F377-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hengartner T, Adams M, Pfister RE, et al. Associations between Red Blood Cell and Platelet Transfusions and Retinopathy of Prematurity. Neonatology 2020;117:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Variation in Performance of Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the United States. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:e164396. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SK, Aziz K, Singhal N, et al. Improving the quality of care for infants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2009;181:469-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schröder C, Schwab F, Behnke M, et al. Epidemiology of healthcare associated infections in Germany: Nearly 20 years of surveillance. Int J Med Microbiol 2015;305:799-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

-

SwissNeoNet Raw Data Items and Definitions -

SwissNeoNet Data Structure - Lawrence AK, Selter L, Frey U. SPHN - The Swiss Personalized Health Network Initiative. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020;270:1156-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010;340:c186. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Timmins N. NHS goes to the PROMS. BMJ 2008;336:1464-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Adams M, Natalucci G, Bassler D; the Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group. An overview of the Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group (SwissNeoNet). Pediatr Med 2023;6:7.