儿童和青少年攻击行为的评估和处理

病例报告

Zoe1,女,9岁,与父母和姐妹(分别7岁和14岁)共同生活,她现在上4年级其中数学是在特殊教育的班级里上。在每年访视中,她妈妈说过去的6个月中她很担心,因为Zoe在家,在学校的行为有问题,就在访视前一周,她妈妈设法拿走她iPad的时候,她变得情绪激动。她乱抓还打她的妈妈,砸坏了iPad的显示屏,并且砸坏了自己的房间。她参加了预约好的今天的访视以消除她妈妈的担忧。

Zoe从三年级中间开始更具有攻击性,且更固执。她每天要花好几个小时用家里的iPad看表演和玩游戏。她妈妈多次发现她把iPad拿走后Zoe还是会看视频到深夜。当她父母亲设法加以限制时,她还大发脾气。这时她会大喊大叫,摔门,扔玩具,身体简直无法控制。她还大喊“我恨你们”和“我死了算了”。她对她的小妹妹不耐烦,推她,还打她。当她没有用电子产品等时,她抱怨说她很烦的。她的妈妈描述她的情绪在容易发怒和愉快中交替往来,认为她每天没有担心,焦虑和悲伤。老师报告说她察觉到学习太困难会感到沮丧。她把她的纸张弄成球形然后扔出教室外。她经常需要1对1的关注才能完成家庭作业。除了数学对她来说一直是个挑战以外,她的分数可以接近或者达到预期。当你单独会见Zoe时,她说她的情绪是“好的”。她否认任何最近的紧张性刺激,包括在家的欺负人或其他改变。她说她的父母亲和小妹妹是讨厌的,她的父母亲拿走她的iPad是不公平的。她承认在学校有时注意力集中有困难,数学太难了。她否认任何自杀的想法。她否认任何伤害他人的想法,但说她打她妹妹的时候会认为“是她妹妹应得的”。

Zoe以前从未看过治疗师或者精神科医生。由于学习上的一些困难,在二年级时她在学校参加了一 项具有个性化的教育计划。无外伤或者药物滥用的证据。她的发育情况在阅读方面有明显的轻度延迟。她没有明显疾病史,她与父母亲和姐妹在家生活。她自从出生由母亲抚养,2岁移民美国后由父亲抚养。她在学校和邻居都有朋友。她看起来比较少和他们面对面相处,但会和他们一起在线上玩游戏。

Zoe穿着她的校服赴约,她前面的短头发是几个月前自己剪的,整个会见过程中她的眼神交流很少,配合性很低。她在检查台上不停地动,还撕纸。她说她的情绪是“好的”,但进一步询问时她说她有时是疯的,悲伤的,或者烦人的。当问及预约这次就诊的原因事件时,她说她不想谈那件事。她否认自杀或者他人的企图。

介绍

攻击性行为影响10-25%年轻人[1],是儿童转诊到精神科的最常见原因[2]。它是精神科疾病的常见症状[3],常处于稳定状态,提示会发展至成人的社会情绪问题[4]。我们将回顾:(Ⅰ)在发育背景下的攻击性行为及其类型(Ⅱ)综合性评估的组成(Ⅲ)综合性治疗的组成(Ⅳ)循证精神疗法(Ⅴ)循证精神药物疗法(Ⅵ)攻击性行为的结局。

方法

为了这篇选择性综述,我们使用检索词“攻击性行为”,“儿童”,“青少年”在MEDLINE上查询了2000至2020年文献。为了精神疗法部分,我们还查询了PsychINFO。另外我们在查询中确认的文章中相关的参考文献我们也进行了查询。这篇稿件不需要IRB的批准。

攻击性行为和发育

学习如何最好地调整攻击性行为是儿童正常发育的一部分。典型的情况是,身体的攻击性行为在18-24个月达到高峰,随着儿童学会自我调整情绪和冲动,到5岁时下降[5]。随着儿童语言技能的发展,他们开始与外界沟通想法和感觉,展现语言方面的攻击性行为[6]。在学龄前期(4-7岁),随着儿童和同伴开始更多的互动,间接性攻击性行为(例如,亲属的和社会方面的)开始增加,特别是女孩[7]。这部分是由于儿童的认知和社会技能的增加,以及他们能认识到这种形式的攻击性行为更少被发现,因此也更少被处罚[8]。随着进入青少年时期,他们会更有自我意识,同龄人的社会立场。他们适应和获得认可的愿望导致增加了对其他儿童和权威人士的攻击性行为,有时是暴力性形式[9]。在鉴别正常攻击性行为和病理性攻击性行为时,注意其强度,频次,伤害以及过程是重要的。攻击性行为持续人生的第一个5年可考虑是异常的[10]。不像正常攻击性行为是暂时的,病理性进攻性行为持续造成混乱,随着时间的推移,常伴有更高的频次和强度[11]。

攻击性行为的类型和原因

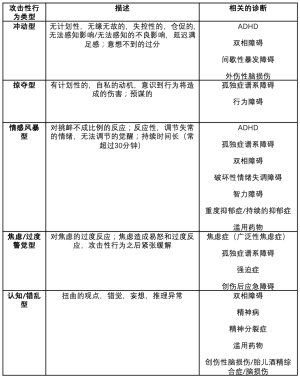

攻击性行为有各种病因,包括遗传性,环境原因,发育性的和病理性的原因,可以是适应性的或适应不良性的。适应性的攻击性行为是正常发育的一部分,起源于中枢神经,服务于亲社会的目的,包括资源的获得,个人或团体的防御,在社会团体中主导地位的确立[12]。有很多方法描述适应不良性攻击性行为,广义上常分为冲动型和掠夺型。冲动型倾向于无计划性和失控性,而掠夺型则是有计划性的,服务于自我的[13]。在最近的一篇综述中,Connor和同事将攻击性行为分出专门的亚型以便进一步鉴别行为类型,包括反应型,冲动型,情感型和掠夺型或主动出击型攻击性行为。反应型常表现为有敌意,对挫折的反应容易改变,而主动出击型攻击性行为是故意的,目的导向的[12]。最后,另外一种有用的分类方法是将进攻性行为分为以下亚型:冲动型,掠夺型,情感风暴型,焦虑/高度警觉型,认知/错乱型[14]。这些分类方法和架构详见表1,由于和生物学机制假说,诊断相关,特别有用。[[14],Kaye DL 2020, personal communication, December 14, 2020]

Full table

当评估一个有攻击性行为的患者时,考虑他的发育情况和攻击性行为的类型很重要。Zoe的行为是伤害性的,超过她的发育阶段预期水平。Zoe看上去是表现为反应型或冲动型。攻击性行为是各种儿童精神病的一种症状,其类型可给予我们找到病因一些线索。在Zoe这个案例中,医生考虑注意缺陷多动障碍(ADHD)或情绪障碍,重度抑郁症,或者持续的抑郁症。下一步给Zoe的整体管理包括综合评估,详见下一章节描述。

综合评估

儿童和青少年的攻击性行为是多种因素导致的结果。所以,当一个儿童或青少年表现攻击性行为时,第一步就是进行综合评估。评估的内容包括(Ⅰ)建立治疗联盟(Ⅱ)收集详细的病史(Ⅲ)分别会见父母亲或监护人和孩子(Ⅳ)纳入和排除相关的精神疾病(Ⅴ)进行风险评估(Ⅵ)从基线开始用评分量表跟踪症状[13]。

治疗联盟

医务人员与儿童及其父母亲建立强大的联盟有利于综合性评估的实施。各种研究强调了建立坚实联盟的重要性以及对改善治疗结局的影响[15,16]。强大的联盟内容包括:了解儿童和父母的优先事项,文化能力,医务人员特征例如增加人与人之间的热情[17]。随着时间的推移,治疗联盟的强度必须再次评估以确保治疗效果。

收集详细的病史

综合性评估的第二步就是从父母或监护人,儿童,老师(获得许可),和其他相关人员收集详细的病史。初期的评估要引出有关顾虑和症状的细节,行为症状的过去史,精神病史,症状回顾,发育史,疾病史,以前的外伤和虐待史,药物使用史和家族史。对于目前的考虑,详细了解发病症状和促发因素非常重要。收集育儿方法,在家庭和学校环境细节方面的信息在进一步评价患者行为的背景上很关键。了解学校的历史和功能特别重要,因为对进一步学校或不同环境的需要可导致儿童行为的控制不良。在发育背景下考虑症状也很重要,例如5岁以前,实际上暂时的和轻度的身体上攻击性行为可以认为是正常的。随着年龄增大,标准的攻击性行为频次减少。当攻击性行为持续或在年龄较大时期发作,这要引起关注。

对Zoe来说,是什么原因导致她攻击性行为加剧还不明确,但是有一些线索。对她来说,设定限制可能是一个诱因,特别是拿走了她的iPad。看起来在家和在学校她变得越来越喜怒无常。她的医生明智地问她关于朋友的问题,例如欺凌和虐待,她全部否认。另一个可能的原因是她在学校的表现和学习困难导致她增加的挫败感。这样,对Zoe来说,她的医生跟她妈妈说带上报告卡,要求老师完成一些评分量表。考虑到Zoe发育时期,到9岁 时,她会发展充分的社会技巧以表达她的感觉和愿望而不诉诸于身体的攻击性行为。她的大发脾气包括大喊大叫,摔门,扔玩具(在生命的前3年可认为是正常的)在她的年龄段是不典型的分别会见父母亲或监护人和孩子如果可能的话,分别会见父母和孩子是很重要的,也要看他们如何互动的。在孩子听不到的情况下分享他们的担忧,父母会感觉更舒服。相似地,儿童和青少年在没有监护人在的情况下更愿意分享敏感的信息例如创伤。在这部分的评估中,外貌,语言,情感,情绪,思维过程,认知过程的洞察力,判断,风险状况(详见下文)用于精神状态检查。另外,观察父母与儿童的互动可以给出他们在家如何相处的线索,这有助于开展有效的介入。

纳入和排除精神疾病和可能的应激源

当一个孩子呈现攻击性行为时, 仔细纳入和排除精神疾病病因和并发病例如ADHD,焦虑性障碍,情绪障碍,智力障碍,滥用药物作为症状的病因或者促发因素很重要。注意风险因素例如社区暴力,朋友的压力,武器的获得途径在制定个体化的治疗方案时可更好地提供给医务人员,表1包含了与攻击性行为相关的不同精神类疾病。

对Zoe来说,从Zoe,她的妈妈,后来从老师那里收集到了更详细的病史,得出结论:她以前患有未诊断的ADHD,注意力问题在学校对她来说是个挑战。除了在家更频繁的爆发外,她还更容易激怒。目前还不明确易怒是否与抑郁轻度或破坏性情绪失调障碍(DMDD)相一致。她的医生决定首先优先处理她的ADHD,监测易怒和攻击性行为。

进行风险评估

对患者进行风险评估是综合性评估的关键部分。保证患者的安全在治疗方案实施前实施中是至关重要的。风险评估包括风险的确立,分析,评估和处理[18]。在考虑患者的精神因素(例如他们的心理健康的现状),社会因素(例如学校和家庭环境,家庭动态),脆弱性,以前自残的病史,暴力,和虐待,药品和武器的获得途径中,风险评估能决定他们的治疗需要和他们伤害自己和他人的风险。这可让医 务人员更高效地与患者家庭和监护人协作促进他们的安全和健康[19]。应该特别注意孩子获得火器和其他武器的途径,因为他们特别关注伤害自己,他人,和冲动性攻击性行为。风险分析涉及考虑增加或降低风险的情况例如药物滥用,个性,保护因素。风险评估涉及评估严重性,持续时间,性质,它提供的信息用于完善适当的治疗计划以促进儿童和家庭的安全。

使用评分量表跟踪症状

评分量表有助于对攻击性行为的基线评估和治疗进展的监测。ADHD,焦虑症,抑郁症的评分量表有助于纳入和排除其他导致攻击性行为的并存情况。攻击性行为量表例如改良攻击行为量表(MOAS)[20]爆发监测量表(OMS)[21],冲动/有预谋的攻击性行为量表(IPAS)[22],儿童的攻击性行为量表-父母亲和教师版(CAS)[23,24]和儿童愤怒的详细清单(ChIA)[25]有助于描述和定量化症状以确定儿童行为的起始点。

综合治疗

给年轻人制定攻击性行为的治疗计划起始于综合评估。如上所述,评估涉及理想化地 在孩子生活中从日间看护者,学校老师和其他成人中获得侧面信息,这在制定治疗计划中也是重要的一部分[13]。治疗计划应该 基于他们的年龄,发育水平,诊断和社会心理背景来满足个体的需要。考虑到攻击性行为常是多因素的,治疗方案也是复杂的,解决多个环境 和精神原因。心理教育与研究治疗中心(CERT)发布的适应不良攻击性行为治疗(TMAY)指南Ⅱ[26]在11个指南共识中有效解决这些问题。下面我们节选和拓展了前5个推荐。

- 向家庭提供或帮助获得循证精神疗法;

- 在实施社会精神策略和实施适当的支持中扮演积极的角色参与到儿童,家庭和学校中;

- 开始精神药物疗法治疗潜在的精神疾病;

- 遵照循证指南治疗原发性(潜在性)疾病;

- 第1-4步以后如果仍然残余攻击性行为,考虑增加一种非典型的抗精神病药物。

其余的CERT指南解释了开立非典型抗精神病药物的安全性细节,这超出了本文的范围。在下两部分,我们 回顾了大部分最新的治疗攻击性行为的精神疗法和精神病药物。

在我们的病例中,Zoe,她的医生首先用兴奋剂治疗她的原发病ADHD。另外,她的医生把 Zoe和她的妈妈转诊到当地的治疗师,治疗师对她妈妈进行父母亲管理培训。两者结合导致Zoe的行为明显改善,所以那段时间,进一步针对Zoe的攻击性行为的精神类药物治疗是不需要的。

下面我们介绍治疗攻击性行为的精神疗法和精神病药物治疗的证据。

遵照循证指南治疗原发病(潜在疾病)

如上所述,攻击性行为是一种和很多精神疾病,社会精神应激源背景下同时发生的症状。这样,在处理攻击性行为时首先我们推荐采用循证的方法解决这些情况和顾虑。例如,如果儿童ADHD治疗有效,他们就会减少冲动,进而减少攻击性。或者如果他们不再抑郁,就会减少易怒,更少的可能在家进行攻击。有些病例这种情况经有效治疗会导致攻击性行为减少。然而,也有一些病例对攻击性行为进行针对性治疗是需要的。

对攻击性行为的精神疗法

研究人员已经发展并评估许多治疗儿童和青少年进攻性行为的精神疗法并证实是有效的。很多方法以社会学习理论和发育原理 为指导,依孩子的年龄做相应的变化。对于幼小的儿童,典型的有效项目包括行为修正,强调帮助父母亲改善亲子互动。对于青少年,很多项目需要青少年自己密切协作,结合认知行为原理去解决他们的适应不良性行为。他们也可以跟父母亲或看护人合作,帮助设定限制和鼓励亲社会的行为。不同的场景(门诊,居家,学校),不管是个体还是群体模式,治疗均表明是有效的。另外,各种精心研究的循证疗法大体上可以分为以父母为中心,以儿童为中心,以家庭为中心,和多种结合模式。下面我们将描述一些最有证据证明有效的疗法。

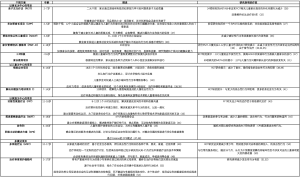

父母为中心项目(学龄前和学龄期)

对于12岁以下儿童,有多个循证疗法已经被证明有效。多数集中在与父母合作,改善他们的技巧,通过有效的情感交流增强亲子关系。许多以父母为中心的治疗被认为是“家长管理培训”,可以是个体或群体模式。治疗师教育家长例如拥有稳定的优质时间,期望行为的积极强化和其他行为管理技术。一些经充分研究的有证据证明治疗攻击性行为有效的项目包括芝加哥家长项目(CPP)[27],亲子互动疗法(PCIT)[28],帮助非依从性儿童项目(NCCP)[29]家长管理培训-俄勒冈模式(PMT-O)[30],积极父母教养课程[31]。表2提供了对含对照的有证据证明疗效的精神疗法的描述。

Full table

以儿童为中心项目

以儿童为的中心项目应用认知行为疗法的元素,聚焦于帮助儿童识别与他们的攻击性行为相关的触发因素,挑战他们的认知洞察力,提高解决问题的能力。两个以儿童为中心项目的循证案例包括愤怒的应对计划[40]和解决问题能力的培训计划[41]

以家庭为中心项目

为了减少儿童攻击性行为,以家庭为中心项目专注于解决家庭成员之间不和谐的相处。在多个场景中,通过学习亲社会技能,例如认知重建和专注聆听来改进成员之间的沟通。另外,在治疗师的指导下,他们处理引起孩子长期攻击性行为的尚未解决的冲突和坏习惯。三项研究最充分的以家庭为中心的疗法包括功能性家庭疗法(FFT)[43]简要战略家庭疗法(BSFT)[44]协作性积极解决方案(CPS)[45]。

多模式精神疗法

多模式精神疗法是指结合不同的治疗方法更好地定制适合孩子的治疗方案。它们通常用于受影响更严重的儿童和青少年。这些疗法采用更复杂,更综合的方法来处理引起儿童适应不良行为的各种因素。一些项目涉及额外的团体,例如学校和司法系统,为儿童创建更加个性化的治疗策略。研究最多的两个循证治疗方案包括多系统治疗[49]和治疗寄养俄勒冈[53]。

精神疗法概要

很多精神疗法在攻击性行为的治疗上有好的证据证实其疗效,行为干预是治疗的关键组成部分。特定的干预类型依患儿的年龄,发育时期,社区的背景和资源而有相应的变化。结合这些疗法作为治疗方案的一部分是很重要的。

精神药物学

如上所述,考虑药物针对性治疗攻击性行为之前,我们推荐综合性评估,使用循证指南处理原发病(包括精神疗法和精神病药物治疗),使用社会心理干预,考虑患儿的年龄和发育情况。例如,当考虑治疗原发病时,许多研究证实在患ADHD,针对ADHD药物也减少攻击性行为。当儿童或者青少年(学龄前期)原发病经足够的精神疗法和药物治疗后仍有严重和伤害性的攻击性行为时,临床医生应该考虑增加药物治疗。当考虑给幼儿(学龄前)药物治疗时需要进一步考虑,诊断评估的过程需要和大龄儿童做细致的比较。Gleason和同事[54]开发了一种算法,都从考虑发育时期和症状变异等的仔细诊断评估开始。治疗推荐非药物干预优于药物干预。在下文中,我们回顾了下面几类药物治疗攻击性行为的循证医学疗效:兴奋剂,α受体激动剂,阿托西汀,选择性5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂,非典型抗精神病药物和情感稳定剂。

兴奋剂

最近20年以来,很多研究证实兴奋剂在治疗儿童ADHD和破坏性行为障碍中减少攻击性行为的疗效。在初诊为ADHD的儿童和青少年中,研究者发现兴奋剂有效减少攻击性行为。Sinzig和同事[55]开展了双盲随机对照试验,比较长效哌醋甲酯(MPH)和安慰剂在ADHD儿童严重攻击性行为和对立违抗性障碍/行为失常(ODD/CD)改善情况, 发现MPH改善在家和学校的对立行为和身体攻击性行为,观察到在学校改善更明显。Connor和同事[56]进行了对兴奋剂治疗儿童ADHD和攻击性行为疗效观察的随机对照试验的Meta分析,发现兴奋剂有效降低攻击性行为,明显的攻击性行为较隐匿的攻击性行为改善更显著。Pringsheim和同事[57]比较了精神类兴奋剂和其它药物在治疗儿童ADHD并发ODD/CD的疗效,发现精神类兴奋剂非常有效,效应大小(ES)为0.84。更早的试验发现不管并发[58]和不并发ADHD ,MPH在治疗儿童CD攻击性行为是有效的。相似的,Pappadopulos和同事[60]在比较各类药物时发现兴奋剂在年轻人各种原发病(ADHD,孤独症谱系障碍(ASD),智力障碍,不管是否并发CD破坏性行为障碍,ODD, ADHD(ES =0.78))中均能有效减少攻击性行为。他们也发现MPH在治疗患ADHD和攻击性行为年轻人特别有效,ES=0.9。儿童注意力缺陷多动症,ODD或CD儿童和青少年破坏性和攻击性行为药物治疗加拿大指南推荐:强有力的药理学证据支持患ADHD和攻击性行为年轻人使用兴奋剂[61]。总之,这些研究提示大量证据支持兴奋剂在治疗攻击性行为上的疗效,特别是但不唯一是患ADHD儿童和青少年。

α受体激动剂

一小部分证据支持使用α2受体激动剂治疗ADHD患儿攻击性行为,或者相关的对立和行为症状。Connor和同事[62]研究了可乐宁, MPH以及联合用药治疗 ADHD和有攻击性行为的ODD或CD患儿的对立症状,结果表明三种治疗均改善 ADHD,CD和ODD症状的严重程度。在一项以后的研究中,Connor和同事[63]研究了胍法辛缓释剂治疗 ADHD和有对立症状的患儿,通过析因分析发现胍法辛缓释剂组对立症状减少。在每项研究中作者都没有特别报道对攻击性行为的影响。Hazell和同事[64]开展了一项关于可乐定作为ADHD合并ODD或CD患儿精神类兴奋剂辅助治疗的RCT研究。他们的研究发现可乐宁较安慰剂有更大比例的攻击性行为改善。Pringsheim和同事[57]报道胍法辛(0.43)比可乐宁(0.27)的ES高,虽然两种药物的ES都低于兴奋剂,见上述。

托莫西汀

还没有表明托莫西汀治疗儿童攻击性行为有效。在一项meta分析中,Pringsheim和同事比较了托莫西汀和精神兴奋剂的疗效,结果发现当治疗ADHD患儿的对立行为,行为问题和攻击性行为时,ADHD的ES低达0.33。相似的,在综述中,Pappadopulos和同事[60]发现托莫西汀在治疗初诊为ADHD和并发疾患的患儿攻击性行为时,总的ES为0.18。有对照研究显示托莫西汀具有改善ADHD症状的效果,没有一项专门评价其对攻击性行为的疗效[65,66]。

选择性5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂

在最近的一项研究中, 研究者比较了西酞普兰和安慰剂添加到MPH单药疗法治疗严重的情绪失调患儿(SMD)的易怒问题,结果表明它减少了儿童和青少年对MPH单药无反应的严重易怒问题[67]。虽然此研究设计是为了探讨SMD的治疗,析因分析表明98%受试者也满足DMDD诊断标准。他们的研究没有专门针对攻击性行为。Armenteros和同事的一项开放性试验证实西酞普兰在治疗不同类型的儿童和青少年原发性精神疾病的冲动性攻击性行为是有效的。

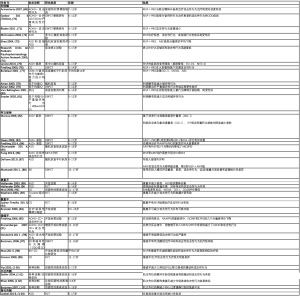

非典型抗精神病药物

研究人员已经开发了第二代抗精神病药治疗攻击性行为,并研究了非典型抗精神病药物在各种疾病相关攻击性行为的应用。请看表3中2000年-2020年抗非典型抗精神病药物治疗攻击性行为和相关情况的RCT研究。最有证据证实疗效的药物是利培酮,常被视为残余攻击性行为的一线药物治疗。利培酮在治疗ASD相关易怒以及儿童CD和ADHD攻击性行为的疗效已经得到确认[72,73,75]。

Full table

虽然不专门针对攻击性行为,几项研究证实阿立哌唑在治疗儿童和青少年ASD中的疗效,一项研究证实阿立哌唑减少双相障碍症的攻击性行为[88]。阿立哌唑和利培酮都有FDA批准的治疗ASD相关易怒的适应症,但对于攻击性行为属于超说明书用药。在美国,没有药物获得FDA批准治疗攻击性行为。在欧洲,利培酮短期(6周)的适应症是低于一般水平的智力功能,智力障碍5岁以上儿童和青少年攻击性行为[105]。

支持其它非典型抗精神病药物治疗攻击性行为的证据是有限的。两项探讨奥氮平治疗攻击性行为的功效,但结果不一[90,92]。一项RCT研究探索氯氮平和利培酮在治疗CD儿童攻击性行为的效果,发现两者都有效[93]。喹硫平,齐拉西酮和卢拉西酮很少有证据支持其使用[97,102,104]。总之,最强有力的证据是利培酮的使用。

和任何治疗一样,考虑何时和是否终止非典型抗精神药物的使用是重要的。研究已经证实利培酮在急性稳定期后继续4个月的短期维持对于防止攻击性行为的复发是获益的[106,107]。治疗指南例如年轻人攻击性行为抗精神病药物使用推荐(TRAAY)强调鉴于治疗风险和副作用,治疗6-9个月后无攻击性行为考虑逐渐减少非典型抗精神病药物的使用[108]。

典型抗精神病药物

由于长期副作用的风险例如迟发性运动障碍,我们不推荐典型/第一代抗精神病药物作为一线治疗。早期的几项对一个新药研究和更多最近的研究支持其功效。Campbell和同事[109]开展了双盲试验,比较了 氟哌啶醇,锂和安慰剂治疗CD攻击性行为型治疗耐受的住院患儿,发现氟哌啶醇和锂在减少行为症状方面均优于安慰剂,但氟哌啶醇与更多的副作用相关。在一个更早的双盲平行队列研究中,Greenhill和同事[110]证实吗啉吲酮在社会化不足CD攻击性行为型住院患儿减少攻击性行为方面与硫醚嗪同样有效。正在开发一种吗啉吲酮更新的缓释配方,SPN-810,用以治疗ADHD和持续冲动性攻击性行为[111]。在一项双盲安慰剂对照试验中,SPN-810添加到目前的ADHD单药疗法和行为疗法中,比安慰剂在改善攻击性行为上更有效[112]。析因分析证实SPN-810治疗冲动性攻击性行为的疗效是通过低缓解率实现的。

抗精神病药物安全性监测

将可能的副作用教会患者和监护人在开任何药物时的重要组成部分,对于治疗攻击性行为药物引起的体重增加和代谢改变的风险,这一点尤其重要。例如,非典型抗精神病药物常引起体重增加和代谢改变,对于健康的生活方式,体重的仔细监测,BMI,胆固醇和血糖要提早教育患者[113]。利培酮会导致血清泌乳素水平升高,医生应该注意监测其症状[114]。对服用氯氮平患者密切监测白细胞计数是很重要的[93]。镇静和嗜睡也是抗精神病药物常见的副作用。

丙戊酸(VPA)

几个研究者探索了VPA在有或者没有发育性障碍儿童攻击性行为中的作用。Donovan和同事开展了小样本双盲安慰剂对照治疗10-18岁年轻人破坏性行为障碍,暴躁的性格和情绪不稳定性的临床试验,结果表明VPA改善攻击性行为和易怒[20]。Steiner和同事[115]在一项研究中将年轻男性CD患者随机分为接受高剂量VPA组和低剂量VPA组,结果证实两组攻击性行为均明显改善,高剂量组在冲动控制方面总有效率和自我报告改善率均高于低剂量组。此项研究缺陷是没有安慰剂作为对照。Blader和同事研究了VPA辅助治疗ADHD患儿经使用兴奋剂后仍残余顽固性攻击性行为的疗效[71,116]。在2009年的研究中,儿童首先用刺激剂治疗,然后将残余攻击性行为患儿随机分为丙戊酸钠辅助治疗组和安慰剂组。结果表明:VPA辅助治疗组更可能获得攻击性行为的缓解。在以后和更大的研究中,他们将刺激剂治疗后顽固性攻击性行为患儿随机分为VPA组,利培酮组和安慰剂组,接受VPA或RISP治疗的患儿较安慰剂组取得更高的攻击性行为缓解率。

两组研究VPA在发育性障碍人群的作用发现:他们的结果不一致。Hollander和同事[117]研究了5-17岁患ASD,外显攻击行为量表和异常行为检查表(ABC)-易怒量表高分儿童易怒和攻击性行为的治疗,发现VPA较安慰剂导致易怒明显改善,但在治疗攻击性行为方面没有统计学明显差异。另外一组研究了VPA治疗6-20岁患广泛性发育障碍(PDD)和明显攻击性行为儿童和青少年的疗效[118],发现VPA在治疗攻击性行为和易怒方面并不比安慰剂更有效。

总的说来,有一些证据支持VPA 治疗兴奋剂单药难治性ADHD,破坏性行为以及发育障碍和攻击性行为儿童攻击性行为的有效性。

锂

Malone和同事发现锂治疗儿童和青少年CD急性攻击性行为较安慰剂更有效[119]。三项更早的RCT研究证实锂减少患CD和慢性,严重攻击性行为的年轻住院患者的攻击性行为症状例如:慢性爆炸性发作,暴力行为,恃强欺弱的行为,打斗和脾气爆发[109,120,121]。

精神药理学结论

在考虑药物治疗攻击性行为之前,我们推荐对原发病进行综合评估,行为干预,循证精神疗法,和抗精神病药物。如果儿童有残余的伤害性攻击性行为,虽然目前没有一个药物获得FDA适应症,多个药物有证据证实是有效的。利培酮和兴奋剂有最多的证据证实其效果,应该被认为是一线治疗用药,紧接其后是丙戊酸钠, 锂和α受体激动剂。西酞普兰也有证据说明治疗DMDD相关易怒是有效的。研究表明阿立哌唑治疗易怒是有效的,但不是专门针对攻击性行为的。对于这些药物,它们会有相关的副作用,所以我们必须衡量其风险和获益。

攻击性行为的结局

童年时期的攻击性行为可能与以后的生活有关。这样,对攻击性行为及时和早期的管理在童年的生活轨迹中扮演重要的角色。很多研究表明剧烈的身体攻击性行为能导致以后的暴力增加[5]。ODD儿童有更大的风险在他们10多岁时发展为CD,这使他们存在更大的风险在成年时期发展为反社会型人格障碍[122,123]。评估少年犯结局的研究,例如匹茨堡青年研究,发现有犯罪行为的年轻些的成年人以后会以更高的频率继续这些行为[124]。其他的研究也表明儿童的攻击性行为与成年的抑郁症和焦虑症的发展存在相关性[125],表明攻击行为与内化和外化障碍之间存在联系。年轻时期的攻击性行为也增加成年时社会功能发展困难的风险。这些人在与家人、重要的人和同龄人的关系中常会有不好的结局[125]。除了社会功能遭到破坏以外,攻击性行为持续至青少年和成年还会负面影响患者的身体健康。一些犯罪学理论已经阐明少年犯和成人身体状况差的关系,包括心血管和神经系统疾病[126]。长期结果证实为了缓解成年时期糟糕的结局,在儿童期早检测,早干预非常重要。

结论

在这篇选择性综述中,我们探讨了攻击性行为的病因和类型,综合性评估和处理的内容,管理年轻人攻击性行为的时机,并总结了攻击性行为最近的循证精神疗法和药物治疗。病因是多方面的,因此,评估应该细致地去做,采用综合性的方法。由于攻击性行为是一个症状,不是诊断或潜在的病因,考虑生物-心理-社会因素的综合评估对于确定最佳的治疗方案是相当重要的。治疗涉及与患儿,家庭建立共同联盟,循证精神疗法和药物治疗原发病以及针对攻击性行为的精神疗法和行为干预。这种方法经常导致攻击性行为减少。然而,如果攻击性行为持续,一些药物已经被证实治疗攻击性行为的疗效。这些药物会伴随着副作用,需要仔细的监测,考虑周期性停药,有了正确的知识和团队,攻击性行为可以在儿科初级保健环境中得到控制。

Acknowledgments

We thank Zoe Paul, M.D. for her contribution of an earlier version of the case description.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Danielle Laraque-Arena and Ruth E.K. Stein) for the series “Integrating Mental Health in the Comprehensive Care of Children and Adolescents: Prevention, Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment” published in Pediatric Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-20-109/coif). The series “Integrating Mental Health in the Comprehensive Care of Children and Adolescents: Prevention, Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. CAG reports grants from PCORI, and royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, outside the submitted work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

1Zoe is fictional case who represents a common presentation of aggression in a child.

References

- Loeber R, Farrington DP. Young children who commit crime: epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Dev Psychopathol 2000;12:737-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pikard J, Roberts N, Groll D. Pediatric Referrals for Urgent Psychiatric Consultation: Clinical Characteristics, Diagnoses and Outcome of 4 to 12 Year Old Children. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27:245-51. [PubMed]

- Nevels RM, Dehon EE, Alexander K, et al. Psychopharmacology of aggression in children and adolescents with primary neuropsychiatric disorders: A review of current and potentially promising treatment options. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;18:184-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kokko K, Pulkkinen L, Huesmann LR, et al. Intensity of Aggression in Childhood as a Predictor of Different Forms of Adult Aggression: A Two-Country (Finland and United States) Analysis. J Res Adolesc 2009;19:9-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hay DF, Castle J, Davies L. Toddlers' use of force against familiar peers: a precursor of serious aggression? Child Dev 2000;71:457-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferris C, Grisso T. editors. Understanding aggressive behavior in children. New York: New York Academy of Sciences. (Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, v. 794), 1996.

- Côté SM, Vaillancourt T, Barker ED, et al. The joint development of physical and indirect aggression: Predictors of continuity and change during childhood. Dev Psychopathol 2007;19:37-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brendgen, Mara. Development of Indirect Aggression Before School Entry. Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development, 2012.

- Lopez VA, Emmer ET. Influences of beliefs and values on male adolescents' decision to commit violent offenses. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 2002;3:28-40. [Crossref]

- Keenan K. Development of Physical Aggression from Early Childhood to Adulthood. Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development, 2012.

- Zahrt DM, Melzer-Lange MD. Aggressive behavior in children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev 2011;32:325-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor DF, Newcorn JH, Saylor KE, et al. Maladaptive aggression: with a focus on impulsive aggression in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2019;29:576-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knapp P, Chait A, Pappadopulos E, et al. Treatment of Maladaptive Aggression in Youth: CERT Guidelines I. Engagement, Assessment, and Management. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1562-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugden SG, Kile SJ, Hendren RL. Neurodevelopmental Pathways to Aggression: A Model to Understand and Target Treatment in Youth. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;18:302-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Pretreatment social relations, therapeutic alliance, and improvements in parenting practices in parent management training. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:346-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Stambaugh LF, et al. Early therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:121-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ross EC, Polaschek DLL, Ward T. The therapeutic alliance: A theoretical revision for offender rehabilitation. Aggress Violent Behav 2008;13:462-80. [Crossref]

- Health Service Executive. Risk management in mental health services. 2009. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/mentalhealth/riskmanagementinmentalhealth.pdf

- The assessment of clinical risk in mental health services. National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH). Manchester: University of Manchester, 2018.

- Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al. Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:818-20. Erratum in: 2000 Jul;157(7):1192 Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:1038.

- Kronenberger WG, Giauque AL, Lafata DE, et al. Quetiapine addition in methylphenidate treatment-resistant adolescents with comorbid ADHD, conduct/oppositional-defiant disorder, and aggression: a prospective, open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007;17:334-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mathias CW, Stanford MS, Marsh DM, et al. Characterizing aggressive behavior with the Impulsive/Premeditated Aggression Scale among adolescents with conduct disorder. Psychiatry Res 2007;151:231-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halperin JM, McKay KE, Newcorn JH. Development, reliability, and validity of the children's aggression scale-parent version. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:245-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halperin JM, McKay KE, Grayson RH, et al. Reliability, validity, and preliminary normative data for the Children’s Aggression Scale-Teacher Version. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:965-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Flanagan R, Allen K. A review of the children’s inventory of anger (CHIA): A needed measure. J Ration-Emot Cogn-Behav Ther 2005;23:263-73. [Crossref]

- Scotto Rosato N, Correll CU, Pappadopulos E, et al. Treatment of maladaptive aggression in youth: cert guidelines ii. Treatments and ongoing management. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1577-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gross D, Garvey C, Julion W, et al. Efficacy of the Chicago parent program with low-income African American and Latino parents of young children. Prev Sci 2009;10:54-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Behavioral Outcomes of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and Triple P—Positive Parenting Program: A Review and Meta-Analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2007;35:475-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon RJ, Forehand, RL. Helping the Noncompliant Child: Family-Based Treatment for Oppositional Behaviour. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, 2003.

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Degarmo DS, et al. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon Divorce Study. Dev Psychopathol 2009;21:637-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nowak C, Heinrichs N. A comprehensive meta-analysis of Triple P-Positive Parenting Program using hierarchical linear modeling: effectiveness and moderating variables. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2008;11:114-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hood KK, Eyberg SM. Outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy: mothers' reports of maintenance three to six years after treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2003;32:419-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forehand RL, Merchant MJ, Parent J, et al. An examination of a Group Curriculum for parents of young children with disruptive behavior. Behav Modif 2011;35:235-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hagen KA, Ogden T, Bjornebekk G. Treatment outcomes and mediators of parent management training: A one-year follow-up of children with conduct problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2011;40:165-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hautmann C, Hoijtink H, Eichelberger I, et al. One-year follow-up of a parent management training for children with externalizing behaviour problems in the real world. Behav Cogn Psychother 2009;37:379-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kjøbli J, Hukkelberg S, Ogden T. A randomized trial of group parent training: reducing child conduct problems in real-world settings. Behav Res Ther 2013;51:113-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bor W, Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C. The effects of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program on preschool children with co-occurring disruptive behavior and attentional/hyperactive difficulties. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2002;30:571-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The coping power program at the middle school transition. Universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychol Addict Behav 2002;16:S40-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lochman JE, Boxmeyer C, Powell N, et al. Dissemination of the Coping Power program: importance of intensity of counselor training. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009;77:397-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lochman JE, Curry JF, Dane H, et al. The anger coping program: An empirically-supported treatment for aggressive children. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 2001;18:63-73. [Crossref]

- Weisz JR, Kazdin AE. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2013.

- Gatti U, Grattagliano I, Rocca G. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments of conduct problems in children and adolescents: an overview. Psychiatr Psychol Law 2018;26:171-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ. Empirically supported family-based treatments for conduct disorder and delinquency in adolescents. J Marital Fam Ther 2012;38:30-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coatsworth JD, Santisteban DA, McBride CK, et al. Brief Strategic Family Therapy versus community control: engagement, retention, and an exploration of the moderating role of adolescent symptom severity. Fam Process 2001;40:313-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ollendick TH, Greene RW, Austin KE, et al. Parent Management Training and Collaborative & Proactive Solutions: A Randomized Control Trial for Oppositional Youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;45:591-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greene R, Winkler J. Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS): A Review of Research Findings in Families, Schools, and Treatment Facilities. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2019;22:549-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greene RW. The explosive child: A new approach for understanding and parenting easily frustrated. Children: Chronically Inflexible. New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

- Greene RW. The aggressive, explosive child. In: Augustyn M, Zuckerman B, Caronna EB. editors. Zuckerman and Parker Handbook of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics for Primary Care. 2nd edition. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, 2010.

- Henggeler SW. Multisystemic Therapy: Clinical Foundations and Research Outcomes. Psychosocial Intervention 2012;21:181-93. [Crossref]

- Weiss B, Han S, Harris V, et al. An independent randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with non-court-referred adolescents with serious conduct problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:1027-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain P, Leve LD, DeGarmo DS. Multidimensional treatment foster care for girls in the juvenile justice system: 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:187-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Westermark PK, Hansson K, Olsson M. Multidimensional treatment foster care (MTFC): results from an independent replication. Journal of Family Therapy 2011;33:20-41. [Crossref]

- McCart MR, Sheidow AJ. Evidence-Based Psychosocial Treatments for Adolescents with Disruptive Behavior. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;45:529-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:1532-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sinzig J, Döpfner M, Lehmkuhl G, et al. Long-acting methylphenidate has an effect on aggressive behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007;17:421-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor DF, Glatt SJ, Lopez ID, et al. Psychopharmacology and aggression. I: A meta-analysis of stimulant effects on overt/covert aggression-related behaviors in ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:253-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:42-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaplan SL, Busner J, Kupietz S, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on adolescents with aggressive conduct disorder and ADDH: A preliminary report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990;29:719-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klein RG, Abikoff H, Klass E, et al. Clinical efficacy of methylphenidate in conduct disorder with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:1073-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pappadopulos E, Woolston S, Chait A, et al. Pharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: efficacy and effect size. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;15:27-39. [PubMed]

- Gorman DA, Gardner DM, Murphy AL, et al. Canadian guidelines on pharmacotherapy for disruptive and aggressive behaviour in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or conduct disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:62-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor DF, Barkley RA, Davis HT. A pilot study of methylphenidate, clonidine, or the combination in adhd comorbid with aggressive oppositional defiant or conduct disorder. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:15-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor DF, Findling RL, Kollins SH, et al. Effects of guanfacine extended release on oppositional symptoms in children aged 6-12 years with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs 2010;24:755-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hazell PL, Stuart JE. A randomized controlled trial of clonidine added to psychostimulant medication for hyperactive and aggressive children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:886-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics 2001;108:E83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michelson D, Buitelaar JK, Danckaerts M, et al. Relapse prevention in pediatric patients with ADHD treated with atomoxetine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;43:896-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Towbin K, Vidal-ribas P, Brotman MA, et al. A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Citalopram Adjunctive to Stimulant Medication in Youth With Chronic Severe Irritability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020;59:350-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armenteros JL, Lewis JE. Citalopram treatment for impulsive aggression in children and adolescents: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:522-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armenteros JL, Lewis JE, Davalos M. Risperidone augmentation for treatment-resistant aggression in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:558-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Molina BS, et al. Risperidone added to parent training and stimulant medication: effects on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and peer aggression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53:948-959.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blader JC, Pliszka SR, Kafantaris V, et al. Stepped Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Aggressive Behavior: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Adjunctive Risperidone, Divalproex Sodium, or Placebo After Stimulant Medication Optimization. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021;60:236-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, et al. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 2002;347:314-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics 2004;114:e634-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: longer-term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1361-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine SZ, Kodesh A, Goldberg Y, et al. Initial severity and efficacy of risperidone in autism: Results from the RUPP trial. Eur Psychiatry 2016;32:16-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Findling RL, McNamara NK, Branicky LA, et al. A double-blind pilot study of risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39:509-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ, Cohen-Kettenis P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of aggression in hospitalized adolescents with subaverage cognitive abilities. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:239-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aman MG, Findling R, Derivan A. 490. Risperidone versus placebo for severe conduct disorder in children with mental retardation. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47:S149. [Crossref]

- Aman MG, De Smedt G, Derivan ARisperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behaviors in children with subaverage intelligence. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1337-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Bellinghen M, de Troch C. Risperidone in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in children and adolescents with borderline intellectual functioning: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001;11:5-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snyder R, Turgay A, Aman MRisperidone Conduct Study Group, et al. Effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:1026-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:1110-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics 2009;124:1533-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Findling RL, Mankoski R, Timko K, et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the safety and efficacy of aripiprazole in the long-term maintenance treatment of pediatric patients with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:22-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghanizadeh A, Sahraeizadeh A, Berk M. A head-to-head comparison of aripiprazole and risperidone for safety and treating autistic disorders, a randomized double blind clinical trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2014;45:185-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fung LK, Mahajan R, Nozzolillo A, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Severe Irritability and Problem Behaviors in Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137:S124-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeVane CL, Charles JM, Abramson RK, et al. Pharmacotherapy of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results from the Randomized BAART Clinical Trial. Pharmacotherapy 2019;39:626-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mankoski R, Zhao J, Carson WH, et al. Young mania rating scale line item analysis in pediatric subjects with bipolar I disorder treated with aripiprazole in a short-term, double-blind, randomized study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2011;21:359-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hollander E, Phillips AT, Yeh CC. Targeted treatments for symptom domains in child and adolescent autism. Lancet 2003;362:732-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hollander E, Wasserman S, Swanson EN, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of olanzapine in childhood/adolescent pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16:541-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masi G, Milone A, Canepa G, et al. Olanzapine treatment in adolescents with severe conduct disorder. Eur Psychiatry 2006;21:51-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephens RJ, Bassel C, Sandor P. Olanzapine in the treatment of aggression and tics in children with Tourette's syndrome--a pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004;14:255-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Juárez-Treviño M, Esquivel AC, Isida LML, et al. Clozapine in the Treatment of Aggression in Conduct Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Trial. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2019;17:43-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kranzler H, Roofeh D, Gerbino-Rosen G, et al. Clozapine: its impact on aggressive behavior among children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;44:55-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Findling RL, Reed MD, O'Riordan MA, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in aggressive children with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45:792-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golubchik P, Sever J, Weizman A. Low-dose quetiapine for adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder and aggressive behavior: open-label trial. Clin Neuropharmacol 2011;34:216-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barzman DH, DelBello MP, Adler CM, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine versus divalproex for the treatment of impulsivity and reactive aggression in adolescents with co-occurring bipolar disorder and disruptive behavior disorder(s). J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16:665-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masi G, Milone A, Stawinoga A, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Risperidone and Quetiapine in Adolescents with Bipolar II Disorder Comorbid with Conduct Disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35:587-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor DF, McLaughlin TJ, Jeffers-Terry M. Randomized controlled pilot study of quetiapine in the treatment of adolescent conduct disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2008;18:140-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yip L, Aeng E, Elbe D. Management of acute agitation and aggression in children and adolescents with pro re nata oral immediate release antipsychotics in the pediatric emergency department. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2020;30:534-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Staller JA. Intramuscular ziprasidone in youth: a retrospective chart review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004;14:590-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan SS, Mican LM. A naturalistic evaluation of intramuscular ziprasidone versus intramuscular olanzapine for the management of acute agitation and aggression in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16:671-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barzman DH, DelBello MP, Forrester JJ, et al. A retrospective chart review of intramuscular ziprasidone for agitation in children and adolescents on psychiatric units: Prospective studies are needed. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007;17:503-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loebel A, Brams M, Goldman RS, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2016;46:1153-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glennon J, Purper-Ouakil D, Bakker M, et al. Paediatric European Risperidone Studies (PERS): context, rationale, objectives, strategy, and challenges. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23:1149-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Findling RL, Townsend L, Brown NV, et al. The treatment of severe childhood aggression study: 12 weeks of extended, blinded treatment in clinical responders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2017;27:52-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Troost PW, Lahuis BE, Steenhuis MP, et al. Long-term effects of risperidone in children with autism spectrum disorders: a placebo discontinuation study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;44:1137-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pappadopulos E, Macintyre JC, Crismon ML, et al. Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part ii. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:145-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campbell M, Small AM, Green WH, et al. Behavioral efficacy of haloperidol and lithium carbonate. A comparison in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984;41:650-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenhill LL, Solomon M, Pleak R, et al. Molindone hydrochloride treatment of hospitalized children with conduct disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1985;46:20-5. [PubMed]

- Stocks JD, Taneja BK, Baroldi P, et al. A phase 2a randomized, parallel group, dose-ranging study of molindone in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and persistent, serious conduct problems. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2012;22:102-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ceresoli-Borroni G, Nasser A, Adewole T, et al. A Double-Blind, Randomized Study of Extended-Release Molindone for Impulsive Aggression in ADHD. J Atten Disord 2021;25:1564-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Correll CU. Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;47:9-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aman MG, Bukstein OG, Gadow KD, et al. What does risperidone add to parent training and stimulant for severe aggression in child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53:47-60.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steiner H, Petersen ML, Saxena K, et al. Divalproex sodium for the treatment of conduct disorder: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1183-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blader JC, Schooler NR, Jensen PS, et al. Adjunctive divalproex versus placebo for children with ADHD and aggression refractory to stimulant monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:1392-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hollander E, Chaplin W, Soorya L, et al. Divalproex Sodium vs Placebo for the Treatment of Irritability in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;35:990-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hellings JA, Weckbaugh M, Nickel EJ, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of valproate for aggression in youth with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005;15:682-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malone RP, Delaney MA, Luebbert JF, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lithium in hospitalized aggressive children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:649-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campbell M, Adams PB, Small AM, et al. Lithium in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder: a double-blind and placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34:445-53. Erratum in: J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34:694. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson GA, Rapport MD, Pataki CS, et al. Lithium in hospitalized children at 4 and 8 weeks: mood, behavior and cognitive effects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1992;33:411-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lahey BB, Loeber R, Burke JD, et al. Predicting future antisocial personality disorder in males from a clinical assessment in childhood. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:389-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB. What are the adolescent antecedents to antisocial personality disorder? Crim Behav Ment Health 2002;12:24-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jennings WG, Loeber R, Pardini DA, et al. Offending from Childhood to Young Adulthood: Recent Results from the Pittsburgh Youth Study. In: Spaaij R, Alvi S, Prowse CE. SpringerBriefs in Criminology. Springer, 2016.

- Burke JD, Rowe R, Boylan K. Functional outcomes of child and adolescent oppositional defiant disorder symptoms in young adult men. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;55:264-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shepherd J, Farrington D, Potts J. Impact of antisocial lifestyle on health. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004;26:347-52. Erratum in: J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:312-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

陆森

江苏省人民医院 主任医师。独立完成普外科各种常规手术,尤其擅长肝移植、肝切除技术。常规开展腹腔镜下胆囊切除术,胆总管探查手术和腔镜肝切除技术,发表SCI文章多篇,主持和参与包括国家自然科学基金在内等多项课题,国家发明专利两项,分别排名: 第二,第四。(更新时间:2022-11-15)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Adesanya DO, Johnson J, Galanter CA. Assessing and treating aggression in children and adolescents. Pediatr Med 2022;5:18.