Health care for children who move in the time of COVID: lack of visibility as a determinant of health

Hundreds of millions of children worldwide are directly affected by migration, having either migrated themselves or having been separated from parents who have migrated. As of April 2020, 33 million children under 18 years of age have migrated across an international border, accounting for 13% of all international migrants (1). Children are more likely to be forced from their homes: half of refugees and 40% of forcibly displaced people are children (2). 153,300 children are known to have migrated without a caregiver; this is thought to be a significant underestimate of the true number of unaccompanied and separated children (2). The number of children globally who are internal migrants, having moved to a new home within the same country, is unknown. However in India alone, 15 million children were living as internal migrants in 2008 (1). Also unknown is the number of children separated from their parents when the parents migrated for education or work, leaving the child in the care of relatives or friends. In China, 69.7 million children are known to be separated from one or both parents in this way (3). All of these children will collectively be referred to in this article as “children who move”, to draw attention away from the reasons for migration or their legal status, and instead focus on the children’s rights and health needs.

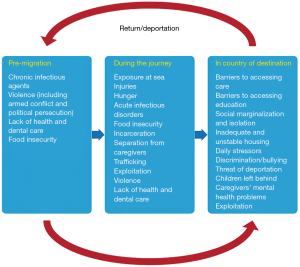

Children who move have particular health needs and risks that are related to the conditions they experience before their journey, during travel, and after they arrive at their destination (Figure 1) (4). While there is increasing evidence on the nature of the health risks and health needs these children face in different contexts, the situation for any individual child depends on their particular story. Human migration is a dynamic process with rapidly changing patterns including changes in where people come from, where and how they travel, and where they settle. The push and pull factors that force or encourage children and families to leave their homes play an important role in determining the kinds of risks that the children will face. A common thread across contexts is that many of the determinants of health for children who move are social in origin and relate to their rights as children; factors such as safety, access to basic needs, access to education, and access to health care all play major roles in children’s short- and long-term health outcomes (5).

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the existing social, economic and health inequalities between migrants and ethnic minority populations compared with majority populations. Studies from the United States and United Kingdom have documented higher incidence of COVID-19 in people of migrant and ethnic minority backgrounds, more severe disease, and elevated mortality (6,7). These patterns have sparked debate about structural racism as a determinant of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 prognosis. The discussions highlight that migrant and ethnic minority groups are at increased risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 due to the kinds of employment they are able to secure, lack of access to personal protective equipment, higher levels of poverty, and crowded living conditions. Barriers in access to care, and worse baseline health status impact the severity of illness and risk of mortality (6,7). At the same time, migrant and ethnic minority groups are being blamed for the pandemic and subjected to overt racism and xenophobia as a climate of fear has taken hold (8-10). This climate of fear brought on by the pandemic has evolved into disturbing trends of othering—differentiating between “us” and “them” in political rhetoric and news media. Public health policies aimed at containing the virus such as border closures and restrictions on movement have reinforced these divisions and stoked racist and xenophobic sentiments.

The pandemic is thought to amplify the social factors that place children who move at risk for poor health and wellbeing (11). Language barriers have become an urgent issue in the context of rapidly changing public health messaging; without clear information in a language that immigrant communities can understand, it is difficult if not impossible for them to follow public health instructions and advice (12). Children who move are more likely to live in crowded households, often with multiple generations living together. This places the children at increased risk of multiple family members become ill with COVID-19, which not only affects physical health but causes psychological distress and places further economic strain on the household due to the costs of health care and loss of income when caregivers are unable to work (11). Pre-existing poverty, caregiver unemployment, lack of furlough and/or sick leave may also lead to worsening poverty and food insecurity for the household (11,13). School closures and online schooling exacerbate the existing barriers to education and deprive children of the opportunity to socialize and play (14). Play is both a critical activity for healthy development and is also a right afforded to children in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (14,15). For children who are offered remote schooling, language may again present a barrier, with caregivers struggling to support remote school participation.

Safety and increased exposure to violence has been an issue of concern for all children, especially during periods of lockdown or severely restricted movement (16). Children who move are known to be at risk of experiencing a broad range of typologies of violence including domestic violence and abuse, community-level violence including interpersonal racism and xenophobia, and structural violence - the harm caused by unfair social arrangements and structures (4,11). The restrictions in movement, social isolation, economic pressures and “othering” of migrant communities give cause for concern that children who move may be experiencing increased violence while they are less visible than ever.

The rapid expansion of the scientific literature on the physical, psychological, and social impacts of COVID-19 will help us to better tackle the disease and its broad-reaching effects. In time, we will also be able to look back at what happened and reflect on our response to the pandemic and what it tells about global human society. One year in, however, it is concerning that there is still very little attention paid to the impact of the pandemic on children who move. When considering structural racism and xenophobia, this poses a more fundamental question about whose lives are considered more important by the scientific community. If we are to successfully tackle systemic racism and xenophobia, we must first identify and acknowledge it everywhere that it exists, even if this makes us uncomfortable about our own role in it. The lack of visibility of children who move, evidenced by a relatively small body of literature on their health and development, has been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. There is an urgent need for research on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and wellbeing of children who move.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Pediatric Medicine. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pm-21-1). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- UNICEF. Child migration. New York. April 2020. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-migration-and-displacement/migration/. Accessed 31 December 2020.

- UNHCR. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019 UNHCR 2020;2020:18.

- Tong L, Yan Q, Kawachi I. The factors associated with being left-behind children in China: Multilevel analysis with nationally representative data. Plos One 2019;14:e0224205 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hjern A, Kadir A. Health of refugee and migrant children. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe 2018.

- ISSOP Migration Working Group. ISSOP position statement on migrant child health. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:161-70. [PubMed]

- Greenaway C, Hargreaves S, Barkati S, et al. COVID-19: Exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. J Travel Med 2020;27:taaa113.

- Nazroo J, Becares L. Evidence for ethnic inequalities in mortality related to COVID-19 infections: findings from an ecological analysis of England. BMJ Open 2020;10:e041750 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheah CSL, Wang C, Ren H, et al. COVID-19 Racism and Mental Health in Chinese American Families. Pediatrics 2020;146:e2020021816 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le TK, Cha L, Han HR, et al. Anti-Asian Xenophobia and Asian American COVID-19 Disparities. Am J Public Health 2020;110:1371-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stone J. England lockdown: Tory MP blames ethnic minorities and immigrants for new coronavirus outbreak. The Independent. 2020 31 July 2020.

- Cholera R, Falusi O, Linton J. Sheltering in Place in a Xenophobic Climate: COVID-19 and Children in Immigrant Families. Pediatrics 2020;146:e20201094 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nezafat Maldonado BM, Collins J, Blundell HJ, et al. Engaging the vulnerable: A rapid review of public health communication aimed at migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. J Migr Health 2020;1:100004 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mukumbang FC, Ambe AN, Adebiyi BO. Unspoken inequality: how COVID-19 has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities of asylum-seekers, refugees, and undocumented migrants in South Africa. Int J Equity Health 2020;19:141. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raman S, Harries M, Nathawad R, et al. Where do we go from here? A child rights-based response to COVID-19. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2020;4:e000714 [Crossref] [PubMed]

-

Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 . - Fore HH. Violence against children in the time of COVID-19: What we have learned, what remains unknown and the opportunities that lie ahead. Child Abuse Negl 2020;104776 [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Kadir A. Health care for children who move in the time of COVID: lack of visibility as a determinant of health. Pediatr Med 2021;4:10.