先天性心脏病患儿喂养:一篇叙述性综述

先天性心脏病(congenital heart disease,CHD)是最常见的出生缺陷,约0.8%的活产婴受此影响,其中许多在婴儿早期需要手术干预[1]。大多数患有CHD的足月新生儿在出生时,体格发育指标测量在正常范围内,但很快就会面临营养问题,使他们处于生长迟缓以及营养不良状态中[1]。生长受限可能会产生大量不良后果,包括心脏手术延期、术后并发症发病率增加以及神经认知发育障碍[2]。本研究综述了CHD患儿的营养问题,包括营养状况的影响因素,并探讨了围手术期的喂养方法,包括能量目标和营养支持,也讨论了CHD患儿这个人群中特殊喂养并发症的处理。

1 方法

我们使用Medline、PubMed数据库对1980年至2020年6月发表的,与患有CHD的婴幼儿营养相关的科学研究进行了检索。通过筛选各研究的标题和摘要,来选择相关文章。对选定论文的参考文献列表也进行了审查,以确定相关研究属于该主题领域。符合条件的研究设计为病例报告、病例系列、队列研究和前瞻性随机对照试验。我们省略了那些非英文文献。审稿人完成了对所选文章全文的评估。

2 CHD患儿的营养学研究

CHD患儿面临生长发育障碍的挑战,测量其体重、身高以及头围增长更为缓慢[3]。急性营养不良导致的初期生长速度降低,与体重增长的减低不成比例,这可以反映在年龄别体重和身高别体重的Z评分值上较低。当营养不良持续存在,患儿的体重/身高会受到影响,同时也会导致更低的年龄别身高的Z评分值,我们称之为生长迟缓。

尽管医学取得了进展,但是营养不良在CHD儿童中仍然很常见[2]。生活在资源充足的卫生保健环境中的CHD患者,急性营养不良的发生率保持在33%~52%之间,并且大约2/3的CHD患者曾经罹患生长迟缓[4-7]。生活在卫生资源有限地区的儿童,营养不良的患病率和严重程度则显著上升,大量研究[8-9]显示该病几乎普遍存在(92%),其中60%被归为重症。年龄越小,营养不良发生率越高,并且表现愈加严重,这与患者所处的医疗环境条件无关。婴儿患有急性营养不良的风险最高(80%),而幼儿组患有生长迟缓的比例与之相近。其他重要危险因素包括由左向右分流或者左心室功能不全引起的充血性心力衰竭症状和慢性紫绀;据报道,青紫型心脏病患儿的生长障碍发生率几乎翻倍(80%发绀,而45%为青紫型CHD)。在资源有限的环境中,贫血也与生长发育不良密切相关,但究竟贫血是微量营养素摄入量不足(如铁耗竭)的表现体征,还是发绀严重程度的反映而非一个独立的病因,这尚不清楚。虽然通常将合并胃肠道结构异常排除在营养研究之外,但是其潜在的综合征和遗传异常可能会进一步导致这类患者的营养不良[10]。

营养不良对术前并发症的发病率影响很大,会导致更高的术后并发症发生率。热量摄入不足会导致内分泌系统、上皮和淋巴系统功能障碍,这可能引起全身免疫缺陷状态、严重感染和死亡的风险随之增加[11-12]。除了直接影响病死率外,术前感染还通过负反馈环使营养问题加重,从而延迟手术治疗,最终导致了额外的感染。当手术在患者营养状况不良时进行,会增加并发症的出现:术后感染和伤口愈合不良,最终导致机械通气支持延长和ICU、住院时间增加[7]。

3 营养状况的决定因素

当能量供应与儿童的基础消耗和生长需求相匹配时,儿童营养健康状态良好。CHD患儿的身体生长发育不良源于代谢的供需失衡,这种失衡是由能量摄入不足、利用和/或吸收效率低下、能量需求增加、遗传生长潜力或上述因素组合所致。

3.1 摄入不足

肠内营养喂养不足是许多CHD患儿生长受限的根本原因。而由胃肠道结构异常引起摄入不足罕见[10]。合并VACTERL综合征和CHARGE综合征的CHD患儿可见食管或肛门闭锁以及气管食管瘘,合并21-三体综合征和非整倍体染色体异常的患者可能患有十二指肠闭锁;心脏异位/异构和肠旋转异常之间也存在很强的联系。在手术治疗期间,肠内营养的长期间隔以及与这些异常相关的残留的胃肠道功能障碍均可导致摄入量不足。

即使没有胃肠道先天性畸形,喂养困难也很常见。在一项横断面调查研究[13]中,近50%的父母因孩子拒绝进食或食欲不良而产生严重焦虑。据1/3的家庭报告称:孩子需要更长的喂养时间和更高的喂养频率。虽然这些挑战贯穿于整个儿童年龄范围内,但是在新生儿和婴儿中尤其常见,因为吞咽协调需要正确的经口喂养,而对于新生儿和婴儿这会更加困难[14]。此外,新生儿吞咽肌张力低下经常被认为加剧了喂养困难。Limperopoulos等[15]发现:需要手术的婴儿中,超过1/4表现出吮吸无力,甚至7%的婴儿完全无法吮吸。这与其他研究[16-17]结论一致:神经系统受损与发绀、肺动脉高压以及复杂CHD 密切相关。在患有肺循环充血、呼吸困难和呼吸费力的儿童中,也可出现吞咽功能不协调。

肠内营养供给不足也可能是由继发于胃食管反流(gastroesophageal reflux,GERD)、胃炎、胃排空延迟,以及肠道缺血或水肿所致胃肠动力不足或者吸收障碍等原因导致的喂养不耐受引发。GERD在CHD患儿中尤其常见[18]。喂养后出现的腹胀或腹部压痛、弯腰、恶心、反复呕吐和便血等症状,可导致看护人员有意减少喂奶数量或停止喂奶。即使喂奶量保持稳定,但是呕吐导致的入量减少也可能导致患儿实际摄入量显著减少。一项研究[19]证明了进食后反复呕吐的严重程度,研究中患有肺淤血的CHD儿童的父母的任务是坚持记录患儿摄入和丢失的结构化日记。他们的记录显示每个孩子每天都会呕吐多次,呕吐量超过10%的摄入量。通过医学治疗来缓解患儿的临床症状,包括严格限制液体摄入量和使用利尿剂,而这有助于减少全身体液总量并减轻肺循环淤血,最终缓解呼吸困难[20]。我们需要通过精细化的护理来达到平衡、优化的液体及热卡摄入量。

在CHD手术后,喂养困难可能会持续存在,甚至偶尔也会加重。在一项观察性研究[21]中,近半数的新生儿在术后无法过渡到经口喂养,需要延长胃管鼻饲喂养的时间。职业治疗师将不能经口喂养归因于患儿吮吸无力或吮吸与吞咽协调不良、反复使用吸引术,或喉部插管[22-23]。这些喂养困难直接与手术复杂性、残余神经损伤、插管时间延长、GERD和声带麻痹相关。声带功能障碍最常见于主动脉弓的手术修复,这可能是由经过主动脉弓以下的左喉返神经损伤引起的;胸腺切除术中也可发生双侧喉返神经损伤。尽管许多人认为Norwood手术是喉返神经损伤风险最高的治疗声带损伤的手术,但是任何包含主动脉弓重建的手术都可能受到类似的影响[24]。虽然许多患者术后喂养困难往往随着时间的推移而改善,但研究其自然病程的很少。在一项小型观察性研究[25]中,在2年的随访中,每5个儿童中有1个报告后遗症,尤其多见于单心室心脏病、神经损伤或早期喂养困难患者。

3.2 能量消耗增加

能量消耗增加在CHD患儿满足其热量需求的供应中起重要作用。最近研究显示,该人群每日总能量消耗增加了28%~35%[19]。在并发有肺淤血的CHD患儿中,代谢需求增加虽然通常归因于心动过速和呼吸费力,但是因为研究未能显示能量消耗增加与充血性心力衰竭(congestive heart-failure,CHF)症状相一致[26],所以其原因尚不明确。对消耗量增加的另一种解释,包括心肌重量增加和儿茶酚胺能神经高紧张状态[27]。无论潜在的病因如何,生长不良都是由能量转化以维持基础代谢率而造成的[19,28]。

3.3 母乳、配方奶粉的替代品和热量密度

包括CHD患儿在内,母乳是所有新生儿的首选。尽管这一人群中的支持数据有限,但是人们普遍认为母乳有更好的耐受性,可促进摄入及生长,并可能与术后并发症减少相关[29]。如果无法进行母乳喂养,通过奶瓶或鼻饲管喂养母乳被认为是最好的替代选择。为了促进母乳摄入,许多地区建立了人乳库,在无法直接母乳喂养或母乳不足的情况下,人乳库能够提供母乳。标准婴儿配方奶粉同样可以使用,并且一般耐受性良好。患有更复杂CHD婴儿普遍患有喂养不耐受,在这种情况下可能需要部分或深度水解配方奶粉。

强化喂养是早期应对能量缺乏和生长障碍的方法,尤其在液体摄入受限时。当人乳可用时,通过添加标准的婴儿配方奶粉,可以增加特别奶/捐赠乳的能量密度。在强化喂养量和/或浓度时,监测宏量营养素和微量营养素的摄入量是很重要的;还可能需要考虑脂肪或碳水化合物合适的比例,以获得最佳的营养支持。通过标准化混合配方比例,向奶粉或奶液浓缩液中添加更少的水,可以得到婴儿配方奶粉能量密度(超过0.67 kcal/mL)。喂养不耐受可能会受到奶粉的能量密度的影响。通过转到水解或元素配方奶可以提升喂养耐受性。通过提供婴幼儿和年长儿高热卡食物也可以达到类似的结果,比如添加脂肪(黄油或餐用稀奶油)制备的浓汤。必须采取护理措施以确保摄入足够的宏量和微量营养素。

3.4 肠内饲管

许多婴儿仅通过口服喂养难以满足他们的营养需求,此时我们需要使用鼻胃管(nasogastric tubes,NG)[30]。当经口喂养有禁忌证时,NG管可用来补充或替代经口喂养,通过这一途径可实现更高的能量喂养。当这种固定的NG管途径替代经口喂养时,可以允许弹丸式喂养或者持续喂养支持,任何一种方法都能有效地提供营养补充。此外,在有症状性CHF儿童中,喂养量的增加会伴随喂养相关的能量消耗减少,最终会使体重增加速率快速改善。胃造瘘置管会提供安全可靠的额外支持[31]。

4 围手术期营养

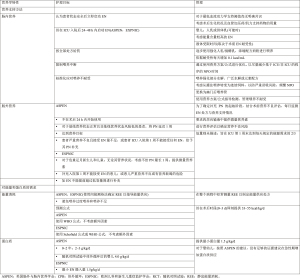

儿童心脏手术后,尽早喂养已被广泛接受,但也提出了一些特殊的挑战。表1总结了美国肠外肠内营养学会(the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition,ASPEN)和欧洲儿科和新生儿重症监护学会(the European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care,ESPNIC)推荐的围手术期营养支持策略[32-33]。入院后48 h内肠内营养(enteral nutrition,EN)的启动一直与重症监护结果的改善相关[34-36]。EN的早期启动有助于减缓肌肉萎缩,促进伤口愈合,并促进内脏血液循环最终避免胃肠道功能障碍,这种障碍即使在短时间饥饿后也可能发生。在没有喂养的情况下,胃肠通透性的增加可导致细菌移位、局部和全身感染,进而加剧术后全身炎症反应[37]。虽然仅有的观察性研究提供了危重症儿童的临床证据,但早期提供EN支持可使肺机械通气概率减少、减缓神经肌肉萎缩、减少血管活性支持,生存率提高[38-41]。即使只提供部分(25%)处方所需能量,也可使患者生存获益,补充能量越多,患者结局改善越明显[41]。疾病严重程度评分较低的年轻患者最有可能受益于早期EN[41-42]。基于这些有限的证据,ASPEN、ESPEN和ESPNIC已经推荐了早期EN[32-33]。

Full table

尽管有证据表明危重症儿童通常喂养耐受性良好,但EN支持延迟却很普遍[43]。一项欧洲对59个儿科重症监护室的调查研究称,仅30%的监护室在手术后12~24 h内开始常规喂养[44]。如果以进入重症监护室后的48 h为界限,监护室内开始喂养率增加至60%[42]。对此,常常将病情不稳定时使用血管活性药物或神经肌肉药物作为一种解释[36,42]。最常受到影响的是那些接受额外外科手术、应用体外膜肺氧合器(extra-corporal membrane oxygenation,ECMO)、需要延迟关胸,或被认为病情不稳定的儿童。尽管人们担心EN可能导致易感患者的内脏缺血,由此推迟喂养,然而由于缺乏关于安全喂养人群的普遍标准或共识,所以医疗实践无统一标准。在缺乏开始EN喂养时血管活性药物明确应用安全标准的情况下,这种临床操作的不一致性尤为凸显。因此,一项大型回顾性研究[45]发现:因担心患者肠系膜灌注不良,其血管活性药物支持水平与其他接受EN治疗的患者相似;而接受喂养的患者和未接受喂养患者的胃肠道并发症无差异。在成人危重症护理试验中,一系列不同的血管活性支持水平在近期证实了早期EN的安全性[46]。通过实施特定机构的指南实施方案或喂养指南,可减少实践操作变异性,由此可以提高早期EN启动的频率[47]。然而,在最近的一项调查中,只有1/3的儿科重症监护室中建立了喂养规范[42]。

4.1 能量目标

在危重症期间,机体生长发育暂时停止,因为基础代谢转移到应对全身炎症反应和组织修复[48]。因此,最佳的营养支持是通过满足总能量消耗和蛋白质需求,以避免患者处于分解代谢状态[49]。然而,儿科重症监护的营养治疗实践来源于有限的数据,而且主要是观察性的试验数据[50]。在急性疾病期间提供充足的营养是至关重要的,但营养过剩可能会增加感染的风险,以及由于二氧化碳产量增加而导致人工通气的时间延长[42]。同样,喂养不足则使全身分解代谢亢进,导致负氮平衡,组织修复减弱,并且延迟身体恢复。在临床中,多重营养缺陷也与感染增加、多器官功能衰竭、住院时间增加与病死率有关[42]。

人们一向认为危重症处于一种由生理应激和剧烈全身性炎症反应引起的高分解代谢状态。能量消耗是根据来自健康儿童群体人体测量的预测公式计算得出,并添加了校正因子来矫正生理应激、体温和身体活动。已经有多个方程已被重新用于确定危重症儿童的能量需求,包括Altman-Dittmer、Harris-Benedict、Schofield、Talbot表、White、世界卫生组织(World Health Organization,WHO)和异速生长量表[51-52]。然而,预测方程的作用随着用于营养科学研究和临床护理的间接测热法的出现而受到了挑战。不同于慢性CHD患儿,术后即刻的静息能量消耗值(rest energy expenditure,REE)显著降低。REE是指在不考虑躯体生长的静息状态期间的能量消耗,术后即刻REE为35~65 kcals/kg/d为预测的40%~60%),始终低于预期的代谢需求[53-56]。能量消耗并不因年龄、潜在的心脏疾病诊断,或手术干预而有明显变化,但与全身炎症反应强度明显相关[42,55,57]。虽然这些研究涉及的样本量小、使用的测量设备和抽样方法不同,但这些成人和儿童的重症监护研究结论高度一致[56]。

权衡考虑临床证据、ASPEN与ESPNIC两大机构对危重症儿童治疗提出的推荐性指南:有条件时,将间接测热法作为确定能量消耗的金标准,以避免喂养过量或喂养不足[32-33]。不幸的是,间接测热法由于成本高昂、需要专用设备和专业培训,通常难以施行。事实上,一项国际调查[58]显示:只有不到20%的儿科重症监护室能够使用这种技术。因此,使用无需校正因子的预测公式被认为是第二最佳选择。关于CHD儿童的最佳预测方程尚未形成统一意见;一项系统回顾建议使用Schofield方程或Talbot表,而其他研究则显示WHO公式计算最精确[51,58]。

4.2 达到能量目标

在危重症儿童中达到足量的EN供给往往具有挑战性,因为营养治疗处方和实际提供的治疗之间存在显著差异。在一项大型队列研究中,只有1/3的处方能量和约40%的处方蛋白质提供给了患者[42]。液体量限制、胃肠道运动功能障碍、喂养中断和主观的胃抽吸量通常是造成这种差异的原因[52]。限制总液体摄入量,通常目的是为了避免与全身性炎症反应相关的术后水肿和肺充血,并且可促进早期拔管。在气道手术操作(插管、拔管)、患者转运和介入治疗时经常中断喂养。值得关注的是,6个月以下的儿童是受到影响最大,而且也是最有可能受到影响的[59]。由多学科团队(包括营养师、护士、医生)实施营养指导仍然是最佳策略,以此可提高能量供给、优化临床结局[60]。值得注意的是,指南在持续关注,正如一项观察性研究[34]发现:所有喂养中断中的大多数(~60%)是可避免的——患者可以在插管和拔管期间保持长时间喂养,除非该患者被诊断为阈值极低的喂养不耐受。

4.3 重新评估能量目标

如前所述,在儿科危重症监护文献中已大量报道了营养不足和不良临床结果之间的联系。最近,越来越多的人了解到系统偏倚潜在可能导致喂养的影响因素中被高估。在所有儿童观察性研究中,固有的选择性偏倚可能将喂养行为与临床结果错误地联系起来,而实际上它仅为一种混杂因素。一般情况良好的患者更有可能早期喂养,更快速地提前进行EN,而且患者并发症也更少;这些患者有更好的临床结局,是因为他们基础健康状况更加良好,而并非因为他们接受了更多的EN。在成人随机研究中同样认识到选择偏倚对于受益高估的影响[61]。

虽然这一结论没有在儿童群体中进行检测,但它已经受到了许多重要的随机化研究的挑战。一项早期的PERMIT研究[62]将EN限制在每日所需能量的40%~60%的成人危重症患者与标准护理(热量要求达到70%~100%所需)患者进行了比较。容许性喂养不足与90 d病死率、感染率和护理中断相关。另一项关于成人急性肺损伤的危重症患者的研究(INTACT)已被迫过早地停止,因为相比于那些接受至少75%能量目标需求的患者,接受更少能量(标准护理)的患者的生存率反而有所改善[63]。因此,结合这些研究结论表明喂养不足可能不会对所有患者有益,但也并不预示着喂养不足对这一组人群会造成伤害。这些差异反映在欧洲指南对喂养不足的不同建议,而北美指南中则没有提及[37,64]。相反,Peake等[65]在一系列随机研究中对增加能量支持的获益提出了质疑,该研究小组首次表明:高能量密度喂养(1.5 kal/mL)可以向危重症成人患者安全地提供近50%的能量,而不增加喂养不耐受的发生率。在一项更大规模的随访研究[66]中,高能量密度喂养与90 d生存率降低或其他任何继发的预见性的并发症无关。虽然没有发现与常规蛋白质摄入相比、更高能量支持喂养更有益处,但是其对于儿童的潜在影响尚未明确。

最新版的ESPNIC指南共识中虽然没有明确提出营养支持的下限,但是可以确定的是,营养支持不应超过REE[32]。

4.4 蛋白质供应

危重症急性期的反应是一系列复杂的代谢改变,这可导致蛋白质分解代谢[67]。炎症反应的强度直接影响机体组织的分解,这可能会更加明显地影响营养储备有限的儿童。在这种急性炎症中,补充满足代谢需求的蛋白质剂量是必要的,这也是目前重症护理营养研究的重点。

儿童从心血管手术后康复的蛋白质需求量,我们知之甚少。在一项研究中,当蛋白质摄入满足分解代谢时,更多蛋白质摄入则更可能达到正氮平衡[68]。尽管蛋白质(中位数1.1 g/kg/d)摄入量变化极大,但达到55~60 kcal/kg/d的能量摄入时,机体即可以实现合成代谢。然而,在另一项关于心肺手术后的婴儿的研究[69]中,使用氮平衡技术评估蛋白质需求时,只有以约4 g/kg/d供应蛋白质,才在术后第3天达到正氮平衡。在缺乏可靠的心脏的具体数据的情况下,从儿科重症监护研究[56,70]中可知:提供1.5 g/kg/d的蛋白质可以实现正氮平衡,但是蛋白质供应范围变化不等,从观察试验中的1.1~2.2 g/kg/d,到随机对照研究中的2.8~4.7 g/kg/d。需要注意的是,较高的蛋白质支持与较低的病死率独立相关[71]。

鉴于数据难以获得,临床实践常以最新版的ASPEN建议中划定的特定年龄的蛋白质需求为指导。0~2、2~13和13~18岁的推荐蛋白质供应量分别为2~3、1.5~2和1.5 g/kg/d[33]。此供应量明显大于相应年龄的膳食营养素参考摄入量(dietary reference intake,DRI),DRI推荐蛋白质摄入量从婴儿的1.5 g/kg/d,到14~18岁青少年的0.8 g/kg/d。相反,近期ESPNIC的建议[32]认为:在新生儿危重症期间,目前尚无足够的证据证明患儿应提供1.5 g/kg/d或更高的蛋白质摄入量,因为无证据表明会获得好的临床效果。

目前,越来越多的成人研究结论相互矛盾,这是围绕蛋白质补充的争论的最好体现。虽然研究虽然已经表明,更高的蛋白质供应和病死率降低、感染减少以及恢复加快相关[72-74],但是另一些研究并没有发现上述结论[75-76]。值得关注的是,最近发表的一篇关于非脓毒症的危重症的论文认为,在危重症患者护理过程中,早期增加蛋白质摄入量与更高的6个月病死率相关[77]。这些研究可能不会直接应用于儿科,但为未来儿童危重症基础营养研究提供了一个重要的框架。

4.5 肠外营养

危重症儿童肠外营养(parenteral nutrition,PN)一直是一个备受关注和争论的话题。支持者认为接受PN治疗将有助于改善先前营养不良患者的预后。然而,在仅有的一项关于这一主题的随机研究中,PEPaNIC研究者报告称:在危重儿童入院后24 h内开始使用PN比仅在入院后7 d后接受PN的预后更差[78]。更早使用PN与更高的医院感染率和更高级别的护理管理(机械通气、重症监护时间和住院时间)相关。其后关于营养不良儿童的研究显示,仅医院感染和重症监护住院时间有类似的减少[79]。同样,对新生儿进行亚组分析,发现其中35%患儿是在实施心脏手术后,其医院感染减少,机械通气时间、ICU住院时间缩短[80]。长期随访显示晚期PN组的行为和认知可能有所改善[81]。尽管不同研究机构的PN使用存在许多局限性和广泛的差异性,但本研究的结果已显示在了关于这一主题的最新ASPEN、ESPEN和ESPNIC指南中[32,33,82]。

4.6 术后追赶性增长

在更好的能量供需平衡条件下,体重增加和生长速率提高在心脏手术后几乎立即开始,并在1年左右达到接近正常值[83-85]。在有更好的营养供应前提下,心脏生理功能迅速恢复正常,几乎同时能量需求出现下降[83,86]。不幸的是,一些患者在手术后仍因营养不良而继续抗争。持续营养不良的危险因素包括显著的心脏残余解剖畸形、术前严重营养不良、低遗传生长潜力(基因异常/综合征、低出生体重和父母身高较低)[83-84]。然而,单心室重建术的纵向研究数据证明,体重获得增加并不总是转化为更好的线性生长[87]。双向空腔肺分流术(Glenn手术)后,年龄别体重Z评分虽然显著改善,但身高增长缓慢导致体重身高比持续升高。虽然有数据表明,较早的心脏修复会使体重恢复更快矫正,但其他的研究又否定了该结论[88]。

5 特殊的注意事项

5.1 乳糜胸

乳糜胸是胸膜腔内乳糜的堆积,是心血管手术的常见并发症,婴儿发生率是2.8%~5%[89]。乳糜液从淋巴系统漏出(通常是胸导管损伤),富含蛋白质、脂肪(包括脂溶性维生素)和免疫球蛋白[90]。从其成分来看,大量丢失可导致液体失衡、电解质紊乱和低蛋白血症相关并发症(凝血功能障碍、蛋白质-能量营养不良、伤口愈合不良和免疫功能受损)[91]。胸腔引流管拔除术后,持续最低/低脂饮食治疗约6周为一线治疗,目的是尽量减少肠系膜淋巴管对脂质的吸收、减少胸导管的回流以促进恢复。还可以尝试用奥曲肽、类固醇或延长禁食期来减少胸导管回流。难治性病例可能需要导管封堵或手术结扎。

婴幼儿乳糜胸的治疗需要将富含长链三酰甘油的牛奶为基础的婴幼儿配方奶粉替换为富含中链三酰甘油的配方奶粉,因其可直接吸收进入门静脉系统。减脂人乳(由离心机得)已被证明,在减少乳糜排出方面与中链三酰甘油配方同样有效,但在前瞻性随机研究中发现减脂人乳与生长不良相关[89,92]。当脱脂母乳中添加附加蛋白后,生长指标得以改善[93]。评估脱脂乳的营养成分的部分研究[94-95]发现:其某些营养成分的浓度较低,而在其他研究中则没有发现差异。在广泛使用脱脂奶之前,应进一步进行营养成分(包括免疫球蛋白)的检测研究。在确定适当的配方替代喂养或强化人乳时,必须针对牛乳蛋白过敏的儿童特别注意产品成分。年长儿必须应用限脂或最低脂肪限制膳食时,该饮食中需要更多的非脂肪膳食食物来源,并增加进餐次数以达到足够的能量摄入,这期间的必须意识到体重增加是有难度的。对于所有饮食中富含中链和缺乏长链三酰甘油的患者,都需要监测并尽可能补充必需脂肪酸和脂溶性维生素。

5.2 坏死性小肠结肠炎

坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis,NEC)是一种以肠道炎症、黏膜完整性破坏、上皮坏死和细菌易位为特征的疾病,而在危重症新生儿的喂养实践中因担心新生儿发生NEC而受到极大影响。尽管足月CHD患儿的NEC发生率(3.3%~6.8%)和临床表现与早产儿相似,但与EN并无关联,足月CHD患儿发生NEC是因为肠道低灌注和内脏缺血,这与早产儿不同[96-98]。单心室患儿(特别是左心室发育不良综合征HLHS)[99]、循环流出道梗阻,以及舒张期分流期病变的婴儿患NEC的风险最高[100-102]。然而,尽管多项研究[99,103]证实EN与新生儿CHD患者患NEC毫不相关,但在围手术期,不同医疗机构间喂养方案存在显著差异。对儿科心脏危重症护理联盟的质量改进登记的分析表明,参与机构中只有一半的新生儿(29%~79%)在心脏手术前接受了喂养[104]。术前喂养与NEC发生率升高无关,甚至可能通过降低全身炎症反应的严重程度来改善术后恢复[93,105]。在易感人群中倡导和推进术后喂养也常常遇到类似的质疑。尽管目前还没有达成共识来指导哪些新生儿可避免肠道缺血并可接受安全的喂养,但使用标准化的喂养方案已被证明,即使在高危人群中,也能在不增加NEC发生率的情况下安全推进喂养[94-95]。因为母乳或捐献人乳对肠道微生物有良好的作用,可促进胃动力、减少肠道炎症,所以一向被鼓励使用。现有的数据不足以支持该人群中NEC发生率的减低[106]。

诊断为NEC的新生儿主要由早产儿构成,治疗方案包括停止EN、启动肠外营养PN支持、使用覆盖肠道病原体抗菌谱的抗生素和外科会诊[107]。而根据临床严重程度不同,可使用液体复苏、使用血液制品,以及肌力或血管活性药物的支持。一旦发生肠穿孔则提示可能需要立即进行手术干预。虽然EN通常使用7~14 d,但是由于重新引入后需缓慢增加喂养,所以肠内的营养影响对患者的影响明显大于经口喂养。

5.3 蛋白质丢失性肠病

蛋白质丢失性肠病(protein losing enteropathy,PLE)是一种罕见的经由胃肠道黏膜蛋白丢失引起的低蛋白血症[108]。PLE是Fontan循环衰竭或CHD右心衰竭最常见的并发症,发生率为3.7%~24%[109]。我们认为,肠系膜充血和血管阻力增高可损害黏膜上皮,增加肠道通透性,并扩张小肠淋巴管。患儿表现为慢性腹泻和喂养不耐受等胃肠道症状,全身表现为低蛋白血症,包括水肿、腹水和/或心包积液[108,110]。PLE可通过检测粪便中的α-1-抗胰蛋白酶,以及α-1-抗胰蛋白酶清除增加来确诊[110]。

PLE相关蛋白营养不良很常见,但饮食干预措施差异很大。饮食建议采用富含蛋白质的高能量饮食,蛋白质摄入量为2.0~3.0 g/kg/d,以支持合成代谢和生长的正氮平衡[111]。如果经口营养素摄入量不足,则可能需要通过NG管进行营养支持,并且在脂肪吸收不良的情况下,应考虑调整脂肪含量的治疗处方(要素或半要素)。在伴有原发性或继发性小肠淋巴管扩张症的儿童中,建议使用含有较少长链三酰甘油和富含中链三酰甘油的饮食[112];中链三酰甘油直接吸收进入门脉系统,可降低淋巴管压力,减少蛋白质渗出。如果口服或通过管饲不能满足营养康复,则需要使用肠外营养治疗。

6 结论

为CHD患儿在患病期间提供足够的肠内营养是一项重大挑战。由于摄入不足、吸收不良、喂养不耐受、能量消耗过多和喂养供应中断等原因导致的热量不足很常见。我们可以通过增加热量密度、引入管饲和辅助治疗来提供补充热量。尽管实践很重要,但因为缺乏设计良好的前瞻性试验,所以主要以回顾性队列研究为指导。围术期的营养管理重点是早期启动并优化肠内营养。基于成人和初步的儿科研究,蛋白质供应是需要补充的主要营养元素,但还需要更多针对儿童的研究。有必要持续评估营养状况(营养不良的风险),以确定适当的有助于儿童的最佳营养治疗方案。很明显,随着营养疗法研究的不断进展,我们需要大规模的前瞻性研究来改善临床结局。

致谢

基金:无。

脚注

出处和同行评论:本文受《儿科医学》出版的《危重症儿童的营养》系列的客座编辑(LyvonneTume, Frederic Valla和 Sascha Verbruggen)的委托。本文由客座编辑和编辑部组织的外部同行评审。

报告清单:作者已经完成了叙述性综述的报告清单。可在https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-20-77/rc上获得。

利益冲突:作者已完成了ICMJE统一披露表格(可在https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-20-77/coif上获得)。《危重症儿童的营养》系列是由编辑部委托制作的,没有受到任何资助或赞助。AAF报告了安大略省政府检验员办公室提交的工作以外的个人费用。作者没有其他的需要声明的利益冲突。

伦理声明:作者对工作的所有方面负责,以确保与工作相关的所有部分的准确性或完整性的问题得到适当的调查和解决。

开放获取声明:这是一篇可以公开获得并可以分享的文章,符合知识共享属性-非商业性- NoDerivs4.0国际许可(CCBY-NC-ND4.0)标准,允许文章的非商业性复制和发布,但严格履行如下条款规定:不允许对原文进行任何修改或编辑,正确引用原文(包括通过相关DOI正式出版链接和许可链接)。参见:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/。

References

- van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2241-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marino LV, Johnson MJ, Hall NJ, et al. The development of a consensus-based nutritional pathway for infants with CHD before surgery using a modified Delphi process. Cardiol Young 2018;28:938-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daymont C, Neal A, Prosnitz A, et al. Growth in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatrics 2013;131:e236-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cameron JW, Rosenthal A, Olson AD. Malnutrition in hospitalized children with congenital heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:1098-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell IM, Logan RW, Pollock JC, et al. Nutritional status of children with congenital heart disease. Br Heart J 1995;73:277-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Longueville C, Robert M, Debande M, et al. Evaluation of nutritional care of hospitalized children in a tertiary pediatric hospital. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2018;25:157-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toole BJ, Toole LE, Kyle UG, et al. Perioperative nutritional support and malnutrition in infants and children with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2014;9:15-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arodiwe I, Chinawa J, Ujunwa F, et al. Nutritional status of congenital heart disease (CHD) patients: Burden and determinant of malnutrition at university of Nigeria teaching hospital Ituku - Ozalla, Enugu. Pak J Med Sci 2015;31:1140-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okoromah CA, Ekure EN, Lesi FE, et al. Prevalence, profile and predictors of malnutrition in children with congenital heart defects: a case-control observational study. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:354-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenwood RD, Rosenthal A, Parisi L, et al. Extracardiac abnormalities in infants with congenital heart disease. Pediatrics 1975;55:485-92. [PubMed]

- Alcoba G, Kerac M, Breysse S, et al. Do children with uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition need antibiotics? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e53184 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rytter MJ, Kolte L, Briend A, et al. The immune system in children with malnutrition--a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e105017 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thommessen M, Heiberg A, Kase BF. Feeding problems in children with congenital heart disease: the impact on energy intake and growth outcome. Eur J Clin Nutr 1992;46:457-64. [PubMed]

- Jadcherla SR, Vijayapal AS, Leuthner S. Feeding abilities in neonates with congenital heart disease: a retrospective study. J Perinatol 2009;29:112-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Limperopoulos C, Majnemer A, Shevell MI, et al. Neurologic status of newborns with congenital heart defects before open heart surgery. Pediatrics 1999;103:402-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varan B, Tokel K, Yilmaz G. Malnutrition and growth failure in cyanotic and acyanotic congenital heart disease with and without pulmonary hypertension. Arch Dis Child 1999;81:49-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis D, Davis S, Cotman K, et al. Feeding difficulties and growth delay in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome versus d-transposition of the great arteries. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29:328-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuwata S, Iwamoto Y, Ishido H, et al. Duodenal tube feeding: an alternative approach for effectively promoting weight gain in children with gastroesophageal reflux and congenital heart disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013;2013:181604 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Kuip M, Hoos MB, Forget PP, et al. Energy expenditure in infants with congenital heart disease, including a meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2003;92:921-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weesner KM, Rosenthal A. Gastroesophageal reflux in association with congenital heart disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1983;22:424-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kogon BE, Ramaswamy V, Todd K, et al. Feeding difficulty in newborns following congenital heart surgery. Congenit Heart Dis 2007;2:332-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Indramohan G, Pedigo TP, Rostoker N, et al. Identification of Risk Factors for Poor Feeding in Infants with Congenital Heart Disease and a Novel Approach to Improve Oral Feeding. J Pediatr Nurs 2017;35:149-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skinner ML, Halstead LA, Rubinstein CS, et al. Laryngopharyngeal dysfunction after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;130:1293-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pourmoghadam KK, DeCampli WM, Ruzmetov M, et al. Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury and Swallowing Dysfunction in Neonatal Aortic Arch Repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:1611-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maurer I, Latal B, Geissmann H, et al. Prevalence and predictors of later feeding disorders in children who underwent neonatal cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young 2011;21:303-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farrell AG, Schamberger MS, Olson IL, et al. Large left-to-right shunts and congestive heart failure increase total energy expenditure in infants with ventricular septal defect. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:1128-31, A10.

- Nydegger A, Bines JE. Energy metabolism in infants with congenital heart disease. Nutrition 2006;22:697-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leitch CA, Karn CA, Peppard RJ, et al. Increased energy expenditure in infants with cyanotic congenital heart disease. J Pediatr 1998;133:755-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cognata A, Kataria-Hale J, Griffiths P, et al. Human Milk Use in the Preoperative Period Is Associated with a Lower Risk for Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Neonates with Complex Congenital Heart Disease. J Pediatr 2019;215:11-6.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vanderhoof JA, Hofschire PJ, Baluff MA, et al. Continuous enteral feedings. An important adjunct to the management of complex congenital heart disease. Am J Dis Child 1982;136:825-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hofner G, Behrens R, Koch A, et al. Enteral nutritional support by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2000;21:341-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tume LN, Valla FV, Joosten K, et al. Nutritional support for children during critical illness: European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) metabolism, endocrine and nutrition section position statement and clinical recommendations. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:411-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, Skillman HE, Irving SY, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Pediatric Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017;41:706-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, McAleer D, Hamilton S, et al. Challenges to optimal enteral nutrition in a multidisciplinary pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2010;34:38-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2003;27:355-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doig GS, Heighes PT, Simpson F, et al. Early enteral nutrition, provided within 24 h of injury or intensive care unit admission, significantly reduces mortality in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:2018-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:159-211. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan V, Hasbani NR, Mehta NM, et al. Early Enteral Nutrition Is Associated With Improved Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Children: A Secondary Analysis of Nutrition Support in the Heart and Lung Failure-Pediatric Insulin Titration Trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020;21:213-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canarie MF, Barry S, Carroll CL, et al. Risk Factors for Delayed Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015;16:e283-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurgueira GL, Leite HP, Taddei JA, et al. Outcomes in a pediatric intensive care unit before and after the implementation of a nutrition support team. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2005;29:176-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mikhailov TA, Kuhn EM, Manzi J, et al. Early enteral nutrition is associated with lower mortality in critically ill children. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:459-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Cahill N, et al. Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically ill children--an international multicenter cohort study*. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2204-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Briassoulis GC, Zavras NJ, Hatzis MT. Effectiveness and safety of a protocol for promotion of early intragastric feeding in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2001;2:113-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tume LN, Balmaks R, da Cruz E, et al. Enteral Feeding Practices in Infants With Congenital Heart Disease Across European PICUs: A European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Survey. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018;19:137-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panchal AK, Manzi J, Connolly S, et al. Safety of Enteral Feedings in Critically Ill Children Receiving Vasoactive Agents. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:236-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wischmeyer PE. Enteral Nutrition Can Be Given to Patients on Vasopressors. Crit Care Med 2020;48:122-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong JJ, Ong C, Han WM, et al. Protocol-driven enteral nutrition in critically ill children: a systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:29-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pierro A. Metabolism and nutritional support in the surgical neonate. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:811-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forchielli ML, McColl R, Walker WA, et al. Children with congenital heart disease: a nutrition challenge. Nutr Rev 1994;52:348-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joffe A, Anton N, Lequier L, et al. Nutritional support for critically ill children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016:CD005144 [PubMed]

- Roebuck N, Fan CS, Floh A, et al. A Comparative Analysis of Equations to Estimate Patient Energy Requirements Following Cardiopulmonary Bypass for Correction of Congenital Heart Disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:444-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogers EJ, Gilbertson HR, Heine RG, et al. Barriers to adequate nutrition in critically ill children. Nutrition 2003;19:865-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Avitzur Y, Singer P, Dagan O, et al. Resting energy expenditure in children with cyanotic and noncyanotic congenital heart disease before and after open heart surgery. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2003;27:47-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gebara BM, Gelmini M, Sarnaik A. Oxygen consumption, energy expenditure, and substrate utilization after cardiac surgery in children. Crit Care Med 1992;20:1550-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zhang G, Herridge J, et al. Energy expenditure and caloric and protein intake in infants following the Norwood procedure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2008;9:55-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bechard LJ, Parrott JS, Mehta NM. Systematic review of the influence of energy and protein intake on protein balance in critically ill children. J Pediatr 2012;161:333-9.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Floh AA, Nakada M, La Rotta G, et al. Systemic inflammation increases energy expenditure following pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015;16:343-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jotterand Chaparro C, Moullet C, Taffe P, et al. Estimation of Resting Energy Expenditure Using Predictive Equations in Critically Ill Children: Results of a Systematic Review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2018;42:976-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keehn A, O'Brien C, Mazurak V, et al. Epidemiology of interruptions to nutrition support in critically ill children in the pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:211-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braudis NJ, Curley MA, Beaupre K, et al. Enteral feeding algorithm for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome poststage I palliation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2009;10:460-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koretz RL, Lipman TO. The presence and effect of bias in trials of early enteral nutrition in critical care. Clin Nutr 2014;33:240-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Haddad SH, et al. Permissive Underfeeding or Standard Enteral Feeding in Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2398-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braunschweig CA, Sheean PM, Peterson SJ, et al. Intensive nutrition in acute lung injury: a clinical trial (INTACT). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:13-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr 2019;38:48-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peake SL, Davies AR, Deane AM, et al. Use of a concentrated enteral nutrition solution to increase calorie delivery to critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:616-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Target Investigators ftACTG, Chapman M, Peake SL, et al. Energy-Dense versus Routine Enteral Nutrition in the Critically Ill. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1823-34.

- Coss-Bu JA, Hamilton-Reeves J, Patel JJ, et al. Protein Requirements of the Critically Ill Pediatric Patient. Nutr Clin Pract 2017;32:128S-41S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teixeira-Cintra MA, Monteiro JP, Tremeschin M, et al. Monitoring of protein catabolism in neonates and young infants post-cardiac surgery. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:977-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Cui YQ, Ma Md ZM, et al. Energy and Protein Requirements in Children Undergoing Cardiopulmonary Bypass Surgery: Current Problems and Future Direction. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2019;43:54-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hauschild DB, Ventura JC, Mehta NM, et al. Impact of the structure and dose of protein intake on clinical and metabolic outcomes in critically ill children: A systematic review. Nutrition 2017;41:97-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Zurakowski D, et al. Adequate enteral protein intake is inversely associated with 60-d mortality in critically ill children: a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:199-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicolo M, Heyland DK, Chittams J, et al. Clinical Outcomes Related to Protein Delivery in a Critically Ill Population: A Multicenter, Multinational Observation Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:45-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrie S, Allman-Farinelli M, Daley M, et al. Protein Requirements in the Critically Ill: A Randomized Controlled Trial Using Parenteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:795-805. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alberda C, Gramlich L, Jones N, et al. The relationship between nutritional intake and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: results of an international multicenter observational study. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1728-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA 2013;310:1591-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Vries MC, Koekkoek WK, Opdam MH, et al. Nutritional assessment of critically ill patients: validation of the modified NUTRIC score. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018;72:428-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Koning MLY, Koekkoek W, Kars J, et al. Association of PROtein and CAloric Intake and Clinical Outcomes in Adult SEPTic and Non-Septic ICU Patients on Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: The PROCASEPT Retrospective Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:434-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fivez T, Kerklaan D, Mesotten D, et al. Early versus Late Parenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Children. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1111-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Puffelen E, Hulst JM, Vanhorebeek I, et al. Outcomes of Delaying Parenteral Nutrition for 1 Week vs Initiation Within 24 Hours Among Undernourished Children in Pediatric Intensive Care: A Subanalysis of the PEPaNIC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e182668 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Puffelen E, Vanhorebeek I, Joosten KFM, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill, term neonates: a preplanned secondary subgroup analysis of the PEPaNIC multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018;2:505-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verstraete S, Verbruggen SC, Hordijk JA, et al. Long-term developmental effects of withholding parenteral nutrition for 1 week in the paediatric intensive care unit: a 2-year follow-up of the PEPaNIC international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:141-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goulet O, Jochum F, Koletzko B. Early or Late Parenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Children: Practical Implications of the PEPaNIC Trial. Ann Nutr Metab 2017;70:34-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaidyanathan B, Radhakrishnan R, Sarala DA, et al. What determines nutritional recovery in malnourished children after correction of congenital heart defects? Pediatrics 2009;124:e294-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weintraub RG, Menahem S. Early surgical closure of a large ventricular septal defect: influence on long-term growth. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;18:552-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosti L, Frigiola A, Bini RM, et al. Growth after neonatal arterial switch operation for D-transposition of the great arteries. Pediatr Cardiol 2002;23:32-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nydegger A, Walsh A, Penny DJ, et al. Changes in resting energy expenditure in children with congenital heart disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63:392-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burch PT, Ravishankar C, Newburger JW, et al. Assessment of Growth 6 Years after the Norwood Procedure. J Pediatr 2017;180:270-4.e6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuurmans FM, Pulles-Heintzberger CF, Gerver WJ, et al. Long-term growth of children with congenital heart disease: a retrospective study. Acta Paediatr 1998;87:1250-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neumann L, Springer T, Nieschke K, et al. ChyloBEST: Chylothorax in Infants and Nutrition with Low-Fat Breast Milk. Pediatr Cardiol 2020;41:108-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGrath EE, Blades Z, Anderson PB. Chylothorax: aetiology, diagnosis and therapeutic options. Respir Med 2010;104:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Floh AA, Slicker J, Schwartz SM. Nutrition and Mesenteric Issues in Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17:S243-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kocel SL, Russell J, O'Connor DL. Fat-Modified Breast Milk Resolves Chylous Pleural Effusion in Infants With Postsurgical Chylothorax but Is Associated With Slow Growth. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:543-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toms R, Jackson KW, Dabal RJ, et al. Preoperative trophic feeds in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Congenit Heart Dis 2015;10:36-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Floh AA, Herridge J, Fan CS, et al. Rapid Advancement in Enteral Nutrition Does Not Affect Systemic Inflammation and Insulin Homeostasis Following Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Bypass Surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020;21:e441-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- del Castillo SL, McCulley ME, Khemani RG, et al. Reducing the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome with the introduction of an enteral feed protocol. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11:373-7. [PubMed]

- McElhinney DB, Hedrick HL, Bush DM, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with congenital heart disease: risk factors and outcomes. Pediatrics 2000;106:1080-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giannone PJ, Luce WA, Nankervis CA, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with congenital heart disease. Life Sci 2008;82:341-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siano E, Lauriti G, Ceccanti S, et al. Cardiogenic Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Clinically Distinct Entity from Classical Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2019;29:14-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Becker KC, Hornik CP, Cotten CM, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in infants with ductal-dependent congenital heart disease. Am J Perinatol 2015;32:633-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies RR, Carver SW, Schmidt R, et al. Gastrointestinal complications after stage I Norwood versus hybrid procedures. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:189-95; discussion 195-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeffries HE, Wells WJ, Starnes VA, et al. Gastrointestinal morbidity after Norwood palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:982-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlo WF, Kimball TR, Michelfelder EC, et al. Persistent diastolic flow reversal in abdominal aortic Doppler-flow profiles is associated with an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in term infants with congenital heart disease. Pediatrics 2007;119:330-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iannucci GJ, Oster ME, Mahle WT. Necrotising enterocolitis in infants with congenital heart disease: the role of enteral feeds. Cardiol Young 2013;23:553-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alten JA, Rhodes LA, Tabbutt S, et al. Perioperative feeding management of neonates with CHD: analysis of the Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium (PC4) registry. Cardiol Young 2015;25:1593-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scahill CJ, Graham EM, Atz AM, et al. Preoperative Feeding Neonates With Cardiac Disease. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2017;8:62-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis JA, Spatz DL. Human Milk and Infants With Congenital Heart Disease: A Summary of Current Literature Supporting the Provision of Human Milk and Breastfeeding. Adv Neonatal Care 2019;19:212-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Speer AL RB, Petty JK. Pediatric General Surgeon and Critically Illl Cardiac Patient. In: Ungerleider RM LJ, McMillan KN, editor. Critical Heart Disease in Infants and Children. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2019:395-405.

- Braamskamp MJ, Dolman KM, Tabbers MM. Clinical practice. Protein-losing enteropathy in children. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:1179-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mertens L, Hagler DJ, Sauer U, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy after the Fontan operation: an international multicenter study. PLE study group. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115:1063-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feldt RH, Driscoll DJ, Offord KP, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy after the Fontan operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;112:672-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:43-9; quiz 50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tift WL, Lloyd JK. Intestinal lymphangiectasia. Long-term results with MCT diet. Arch Dis Child 1975;50:269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Herridge J, Tedesco-Bruce A, Gray S, Floh AA. Feeding the child with congenital heart disease: a narrative review. Pediatr Med 2021;4:7.