Psychosexological evaluation of children with precocious puberty: an interview study focusing on parental perspective and reasons for delaying treatment of their children

Introduction

Precocious puberty (PP), defined as the appearance of secondary sex characteristics before the age of 8, or the premature onset of menarche before the age of 9, affects an estimated 1 and 5,000 children (1). It is often difficult to diagnose first changes associated with PP, especially among girls. The reason is that changes in physical appearance largely depend on the level of hormonal changes, combined with genetic predisposition. PP may be defined as gonadotropin-dependent, progressive, or gonadotropin-independent (2). The earliest neuroendocrine changes associated with signs and symptoms of PP is increased kisspeptin secretion from the arcuate nucleus and the anteroventral paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (3). Existing literature consistently shows that the environment within certain parts of the world, like the United States, predisposes teenagers to experience puberty much earlier than children in Europe or Asia. Consequently, changes associated with PP tend to show up much earlier among American children and it might be much more difficult to arrive at the appropriate differential diagnosis.

Since puberty can occur so early, it is not surprising that many parents are concerned when their children exhibit rapid growth spurt. Timely medical intervention is required to achieve a successful treatment outcome, yet many parents might delay evaluation and treatment due to social-cultural concerns (4). One of the most commonly reported reasons for delaying treatment is the fear of hormonal therapy. Generally, parents have been informed by neighbors or close friends that hormonal therapy has negative consequences and that increased growth spur is typical for some children. Therefore, it is easy for modern parents to dismiss the signs and symptoms of PP in place of alternative health advice (5).

Currently, there are plenty of treatment options available to ameliorate the symptoms of PP. Among the most effective treatment medications are the long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog (GnRHa) and leuprolide acetate (6). In addition to medical treatment, children can work with a psychologist to decrease anxiety associated with worrying about unusual physical changes. Despite available evidence, we do not precisely know how much information parents have about the signs and symptoms of PP, how they search for help, and what kind of social and cultural barriers prevent them from getting their children into medical treatment promptly.

This study investigated the perceptions of parents whose children are going through PP. The reason why we identified this topic for research is that it directly affects the quality of care that children can expect to receive. When parents are convinced that their children’s abnormal growth development doesn’t require medical treatment, they are less likely to schedule a medical consultation with a healthcare provider. Therefore, we were interested in understanding what factors might delay treatment, how parents deal with anxiety associated with changes in their child’s physical development, and what are the expected long-term outcomes.

Methods

The primary mode of analysis is interview series, complete with 10 couples (M =5, mean age =37; F =5, mean age =33) who came in for treatment with their child for PP. There were no specific inclusion criteria, aside from having a child actively participating in therapy in our clinic for PP. We were interested in understanding what it’s like for parents to support their children while their body goes through various changes due to deregulated normal physiological development. Knowing this information has significant implications for medical practice, and allows medical providers to understand what kind of psychological trauma parents might go through when trying to help their child face the reality of changing physical body due to developmental imbalance.

Data collection

The data were collected in our clinic between June and August 2018 in Poland via video-conference. Each interview lasted one hour and was recorded and transcribed verbatim. All transcripts went through qualitative data analysis, using principles of the grounded theory (7). At the end of the analysis, we identified three themes and explained each one with great detail in the results section of the manuscript.

Study population

The study population includes 10 heterosexual couples (M =5, mean age =37; F =5, mean age =33). Eight couples were married while the remaining two were cohabiting in a committed relationship. The mean time of being in a relationship was 5.6 years for married couples and 3.4 for unmarried couples.

Ethics

The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee.

Results

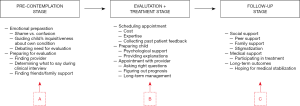

In our analysis, we identified three themes that summarize the context of the discussions that we’ve had with our participants: pre-contemplation stage, evaluation and treatment stage, and follow-up stage. All the main findings are summarized in Figure 1.

Pre-contemplation stage

In this stage (denoted as Point A in Figure 1), parents who seek help for their children face difficulties related to emotional preparation and getting their child ready for medical evaluation. Emotional preparation tends to be difficult for nearly 89% of our respondents as they are feeling ashamed and confused about what is going on with their child’s body. Most of them admit that they have been influenced by what they’ve seen on the social media, television, and hearing stories from friends. To them, having a child that has PP was somewhat a bad omen, something unexplainable. The biggest problem is remaining supportive towards own child, while also facing the reality of undesirable physical appearance of their loved one. Over 80% of parents reported feeling discomfort with discussing their child’s sexuality with a medical provider. The main reasoning is that these parents felt like their child’s development is different from the norm—and it is indeed different from how they were growing up. Therefore, these parents tend to debate whether there’s any need for evaluation.

Once parents determine that there is a need for medical evaluation, the main problem that becomes obvious is identifying the appropriate medical provider. It’s not just a matter of finding someone, whose expertise is desirable, but also someone who can offer actionable advice. Because the matter concerns the child’s sexual development, three-quarters of our participants said that they felt uneasy about identifying what kind of questions they should ask during their child’s medical evaluation. Some of our participants reported seeking help and advice from family and friends, but most said that they refrained from engaging too many individuals in discussing their child’s PP. The most frequently cited reasons are the feeling that people would be judgmental, that they would label their child as underdeveloped, possibly implying that their child could have trouble with normal sexual functioning in the future.

Evaluation and treatment stage

In this stage (denoted as Point B on Figure 1), parents typically commit scheduling appointment with a medical provider to obtain more information about what causes their child’s PP. There’s an obvious concern here that the medical provider might give the parents some bad news. Therefore, the level of anxiety and fear is the highest at this stage of seeking treatment for child’s PP.

The first obstacle facing most parents is identifying a provider whose services are affordable. While 80% of our participants reported seeking help from their child’s pediatrician, the rest decided to try advice from an expert in the field of sexual medicine, hoping that this type of expertise what help their child much more than general pediatric practice. One way of identifying the appropriate provider is by seeking feedback from past patients from online discussion sites, including Facebook groups. This seems to be the most popular way of finding doctors that can handle pediatric cases of PP. Another interesting method reported to us was reading through research papers about PP, and identifying doctors who wrote these publications and who might have specialized expertise in treating this condition. The reason why parents often go beyond reasonable methods of determining appropriate medical provider for a somewhat common pediatric problem is the fear that untreated pathological sexual development is going to change their child’s life forever negatively.

The next obvious problem is preparing the child for their medical appointment. Parents in our sample were expecting that their children will be somehow devastated that their body is not developing the same way as their peers. Therefore, mothers tend to report investing the significant amount of time in psychologically preparing their child for facing the reality of dealing with unusual physical changes that come with PP. Once they schedule the appointment with a medical provider, the parents play a significant role in serving as an information resource for their child. Nearly 70% of our participants reported Reading expert literature to understand better what is PP, what causes it, and what are the implications for healthy child development. Fathers were especially interested in serving as guides for their children. The reason was that they felt that any physical changes in their child’s appearance might hinder their ability to have a successful dating life. Therefore, they felt encouraged to take full ownership of providing as many resources to their children as possible.

During the evaluation process, most parents reported the distress associated with how their child might feel about rapidly changing physical body. There is much anxiety concerning whether children can engage in any harmful behaviors as a result of their dissatisfaction with physical development. Another source of stress is associated with figuring out whether PP can be successfully treated before anyone notices physical changes. There’s the concern about any side effects that might result during hormonal therapy. Most parents in our sample were worried that the kids would go through some psychological trauma, would refuse to inform their parents about any concerns they might have. Therefore, it was very important for over 80% of our participants to establish reliable communication with their child to facilitate problem-solving.

Follow-up stage

In this stage (denoted as Point C in Figure 1), parents are mostly concerned about following up on the medical care of their child. Their primary motivation is to maintaining strong social support, consisting of the peer network, family support, and removing any sources of stigmatization. At this stage, most parents could observe treatment progression for their child and are much more optimistic about the treatment outcome. There continue to be concerned about any long-term effects of PP. However, one of the most critical goals for parents to achieve is to ensure that their children can successfully move on, and forget about what kind of adverse changes their physical body has gone through.

Discussion

This study attempted to understand the perspective of parents seeking treatment for children who have PP. From a sexological perspective, it is essential to know how abnormal sexual development affects the quality of family dynamics. As we know from sociological evidence (8), studies have shown that developmental concerns often strain the quality of interaction between different family members. Concerning the PP, many parents might be concerned about what will happen to the quality of life of their children as they grow up. Not coincidentally, because PP concerns the visible changes in how children develop physically—the whole situation might create uneasiness about addressing this medical problem. Some parents might be even ashamed that their children are not growing properly, and also might seek to conceal the developmental issues of their children.

Another important issue concerns how we talk about the disorders of healthy sexual development. Most people feel a little bit uneasy when seeing a physician and talking about specific concerns regarding sexual function (9). The problem can be specifically challenging when similar issues face children; some parents might not be ready to maturely and effectively seek professional medical help. For instance, we know from research that many parents feel shame when their male child might have hypospadias (10) as it is a sign of developmental malfunction. In the society that values sexual vitality, it is not surprising that healthy sexual development is desirable by every single parent.

The method applied in this study involved the use of semi-structured interviews to understand the parental perspective on what it is like to have a child with PP. Aside from collecting the necessary demographic information, we did not attempt to conduct any psychological testing or obtain the kind of data that would allow us to perform statistical analyses. The reason is that we were only interested in understanding what kind of social, financial, and knowledge barriers face parents, whose children are not developing appropriately.

The results identify three themes that explain obstacles facing parents of children with PP: pre-contemplation stage, evaluation and treatment stage, and follow-up stage. These data show that having a child with PP creates several challenges for parents and the child itself. First, parents are worried that their children might not be able to develop correctly, which would have negative consequences on their ability to date and establish romantic partnerships. Second, parents are worried that their children might be faced with social stigmatization among their peers, neighbors, and family. The reason is that parents often believe that signs of PP indicate severe developmental concerns and the physical changes itself are a source of unwarranted scrutiny. Third, depending on the parent’s comfort level with talking about the disorders of sexual development, some parents choose to postpone the medical treatment for their children: for some, they are concerned about the cost of treatment, while others think that giving children hormones will hurt their further development.

The data presented here are highly applicable to the clinical practice of pediatricians, internal medicine providers, endocrinologist, and parents alike. The information discussed here should serve as a guideline for commencing a conversation with parents, who are usually very concerned about the physical changes that occur as a result of PP. Many of them are very frightened about possible adverse health outcomes for their children. While these concerns are usually overstated, as physicians we are required to create a conversational environment of support and information. This way parents can be assured that PP can be managed medically without creating adverse outcomes.

This study has several strengths and limitations. The greatest strength of the data presented here is that it is based on the interviews of 10 couples, who came into a specialized sex medicine clinic to treat their children’s PP. Therefore, we get to learn about the financial, social, and medical information limitations that often make parents anxious about putting their children through hormonal treatment. The primary limitation of this study is its sample size as well as the mode of analysis. Since we did not collect any survey responses, we were not able to show any statistical analyses or perform correlation analyses. However, the purpose of our study was to collect information through a semi-structured interview and to present the results in a qualitative form.

Future research should further explore what the challenges facing parents who have children with PP are. In particular, we need to understand what kind of resources are usually available to parents and whether any specific social factors might limit their interest in bringing their children to the medical provider for treatment. As we have identified in this study, parents are often ashamed that their children are not developing physically just as their peers do, prompting some to postpone treatment. These are serious concerns that stem from parental lack of knowledge about what causes PP. Therefore, it is worth investigating public health remedies to educate the public about the need to participate in treatment when there are visible signs of increased physical maturation.

Conclusions

The study presented here investigated the perspective of parents of children who are experiencing the signs and symptoms of PP. We find that many parents feel that their children are going to be socially stigmatized because of their increased physical growth. Furthermore, some parents are uneasy about putting their children through hormonal treatment due to concerns that it might cause irreversible physical changes. Given these constraints, it is essential for medical providers to recognize the strong social influences on parental decision-making when it comes to treating their children’s PP. There seems to be the overwhelming misunderstanding of the signs and symptoms of PP and its implications for further development. Therefore, medical providers need to invest time in carefully educating parents about the benefits of treatment.

Acknowledgments

The source of funding comes from the Ministry of Health.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pm.2019.04.05). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee (No. 2017/25/AB72). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cesario SK, Hughes LA. Precocious puberty: a comprehensive review of literature. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2007;36:263-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berberoglu M. Precocious puberty and normal variant puberty: definition, etiology, diagnosis and current management. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2009;1:164-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fuqua JS. Treatment and outcomes of precocious puberty: an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:2198-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bajpai A, Menon PS. Contemporary issues in precocious puberty. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2011;15:S172-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brito VN, Spinola-Castro AM, Kochi C, et al. Central precocious puberty: revisiting the diagnosis and therapeutic management. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2016;60:163-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clemons RD, Kappy MS, Stuart TE, et al. Long-term effectiveness of depot gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in the treatment of children with central precocious puberty. Am J Dis Child 1993;147:653-7. [PubMed]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1967.

- Golics CJ, Basra MK, Finlay AY, et al. The impact of disease on family members: a critical aspect of medical care. J R Soc Med 2013;106:399-407. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson J. ABC of sexual health: taking a sexual history. BMJ 1998;317:1573-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rolston AM, Gardner M, Vilain E, et al. Parental Reports of Stigma Associated with Child's Disorder of Sex Development. Int J Endocrinol 2015;2015:980121 [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Sendler DJ, Szewczyk A. Psychosexological evaluation of children with precocious puberty: an interview study focusing on parental perspective and reasons for delaying treatment of their children. Pediatr Med 2019;2:15.